Longitudinal Physiological Monitoring and Evidence-Based Training Periodization in Junior Cross-Country Skiers: A Three-Season Case Study

Category: Sports Science

Purpose: This longitudinal case study examined the efficacy of systematic physiological monitoring in guiding individualized training periodization for junior cross-country skiers across three consecutive competitive seasons.

Methods: Six male junior cross-country skiers (age 15.3-18.7 years) from a regional sports academy underwent quarterly laboratory testing on a cycle ergometer, including determination of anaerobic threshold (AnT) via ventilatory breakpoint, maximal alactic muscular power (MAM) via 6-second sprint, stroke volume (SV) estimation via HR-power extrapolation, and daily heart rate variability (HRV) monitoring. Training zones were individually prescribed and dynamically adjusted based on test results.

Results: Over three seasons, mean AnT power increased 16.9% (225 +/- 18 to 263 +/- 22 W; Cohen's d = 1.87), MAM increased 30.8% (650 +/- 45 to 851 +/- 62 W; d = 3.70), and estimated VO2max improved 14.8% (58.2 +/- 3.1 to 66.8 +/- 2.9 mL/kg/min; d = 2.78). Ventilatory threshold showed strong agreement with blood lactate measurements (r = 0.91, mean difference = 6.2 W). A targeted SV training protocol produced measurable SV increases in four of six athletes. HRV monitoring enabled early detection of functional overreaching in two athletes, prompting training modifications that prevented progression to non-functional overreaching. Individual response patterns varied substantially, underscoring the necessity of personalized training approaches.

Conclusions: Systematic physiological monitoring integrated into a coaching feedback loop can guide effective individualized training periodization in developing endurance athletes. The ventilatory threshold method provides a practical, non-invasive alternative to blood lactate testing for training zone determination.

Category: Sports Science

Cross-country skiing is among the most physiologically demanding endurance sports, requiring exceptional aerobic capacity, muscular endurance, and metabolic efficiency across varying terrain and climatic conditions. Elite cross-country skiers consistently demonstrate among the highest recorded maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) values in sport, with values exceeding 80 mL/kg/min reported in male world-class competitors (Losnegard & Hallen, 2024; Sandbakk & Holmberg, 2022). The development of these exceptional physiological capacities begins during the junior training years, making this period critical for long-term athletic development.

Despite the recognized importance of individualized training in endurance sport development, systematic longitudinal monitoring of junior cross-country skiers remains surprisingly underrepresented in the literature. Most existing studies are cross-sectional in design, comparing physiological profiles across competitive levels or age groups at a single time point (Roczniok et al., 2023; Sjodin et al., 2022). Fewer studies have tracked individual physiological trajectories over multiple seasons, and fewer still have documented how monitoring data were translated into specific training decisions in real time.

Laboratory-based exercise testing provides the most rigorous approach to quantifying training-induced physiological adaptations. Cycle ergometry, while not sport-specific to skiing, offers standardized, reproducible conditions for assessing key performance determinants including anaerobic threshold (AnT), maximal power output, and cardiovascular efficiency (Haugen et al., 2022). The anaerobic threshold, variably defined by ventilatory, blood lactate, or gas exchange criteria, is widely recognized as the single most important determinant of endurance performance and the primary target for training-induced improvement (Casado et al., 2023; Haugen et al., 2021).

Beyond threshold assessment, several physiological markers have been proposed as indicators of training status in endurance athletes. Maximal alactic muscular power (MAM), reflecting phosphocreatine system capacity, provides information about sprint and neuromuscular function that complements aerobic measures (Losnegard & Hallen, 2024). Stroke volume (SV) estimation through heart rate-power relationships offers insight into cardiac adaptation, a key driver of VO2max improvement in young athletes (Vaccari et al., 2023; Tremblay et al., 2024). Heart rate variability (HRV), assessed through time-domain and frequency-domain analysis of R-R intervals, has emerged as a practical tool for monitoring autonomic balance, recovery status, and training load tolerance (Plews et al., 2022; Schmitt et al., 2021).

The integration of multiple physiological markers into a coherent monitoring framework -- one that informs day-to-day training decisions rather than merely documenting post-hoc adaptations -- represents the current frontier in applied sport science (Hecksteden et al., 2023). Such integration requires not only valid and reliable measurement tools but also interpretive frameworks that translate physiological data into actionable coaching recommendations.

The present study addresses this gap through a detailed three-season case study of six junior cross-country skiers who underwent systematic physiological monitoring with continuous feedback to coaching staff. The primary aims were to: (1) document the magnitude and time course of physiological adaptations across three developmental seasons; (2) validate the ventilatory threshold method against blood lactate measurements in this population; (3) evaluate the utility of stroke volume training and HRV monitoring in guiding individualized training; and (4) describe how physiological monitoring data were integrated into coaching practice.

Six male junior cross-country skiers (age at enrollment: 15.3-18.7 years) were recruited from a regional sports academy in northern Russia. All athletes competed at the regional or national junior level and had a minimum of two years of systematic training history. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and, where applicable, their legal guardians. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

| Athlete | Age S1 (yr) | Age S3 (yr) | Mass S1 (kg) | Mass S3 (kg) | FFM S1 (kg) | FFM S3 (kg) | BF S1 (%) | BF S3 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 18.7 | 20.9 | 62.4 | 64.1 | 56.8 | 59.2 | 9.0 | 7.6 |

| B | 17.2 | 19.4 | 58.6 | 61.3 | 52.1 | 55.8 | 11.1 | 9.0 |

| C | 16.5 | 18.7 | 60.1 | 63.7 | 53.4 | 58.5 | 11.1 | 8.2 |

| D | 15.8 | 18.0 | 55.3 | 60.8 | 48.7 | 55.4 | 11.9 | 8.9 |

| E | 16.1 | 18.3 | 57.8 | 62.5 | 51.6 | 57.3 | 10.7 | 8.3 |

| F | 15.3 | 17.5 | 53.2 | 58.9 | 46.5 | 53.2 | 12.6 | 9.7 |

| Mean+/-SD | 16.6+/-1.2 | 18.8+/-1.2 | 57.9+/-3.3 | 61.9+/-1.9 | 51.5+/-3.6 | 56.6+/-2.3 | 11.1+/-1.2 | 8.6+/-0.7 |

Table 1. Participant Characteristics at Baseline (Season 1) and Final Assessment (Season 3). FFM = fat-free mass; BF = body fat percentage.

Laboratory testing was conducted on a mechanically braked cycle ergometer (Monark 828E, Vansbro, Sweden). Testing was performed at four standardized time points per season: (1) pre-season baseline (September), (2) mid-season (December), (3) competition peak (February), and (4) post-season (April). The incremental test protocol began at 100 W with 25 W increases every 2 minutes until volitional exhaustion. Continuous respiratory gas exchange was measured using a portable metabolic analyzer (MetaLyzer 3B, Cortex Biophysik, Leipzig, Germany) calibrated before each test. Heart rate was recorded continuously using a Polar S810i monitor (Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland).

The anaerobic threshold (AnT) was identified using the ventilatory breakpoint method, defined as the power output at which a disproportionate increase in ventilation relative to workload was observed, corresponding to the second ventilatory threshold (VT2). The ventilatory equivalents for oxygen (VE/VO2) and carbon dioxide (VE/VCO2) were plotted against power output; the AnT was determined as the power output at which VE/VCO2 began to rise while VE/VO2 continued to increase. Two independent reviewers determined threshold values, with disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. On a subset of 24 tests, blood lactate was simultaneously measured from fingertip capillary samples at the end of each workload stage for cross-validation.

MAM was assessed using a 6-second all-out sprint on the Monark 828E ergometer with a braking force of 7.5% body mass. Athletes performed a standardized warm-up (5 minutes at 100 W followed by two 3-second sprints) before three maximal 6-second efforts separated by 3-minute rest intervals. The highest peak power value across the three trials was recorded as MAM.

Potential VO2max was estimated using the HR-power relationship extrapolation method. The linear portion of the HR-power curve (typically between 120 and 170 bpm) was extrapolated to the age-predicted maximal heart rate (220 minus age). The corresponding power output was then converted to VO2 using the established cycle ergometry equation (VO2 = [10.8 x Power/Mass] + 7). Stroke volume at submaximal workloads was estimated using the Fick principle rearrangement: SV = VO2 / (HR x a-vO2diff), where a-vO2diff was assumed constant at 15 mL/100 mL at moderate intensities (Hoffmann et al., 2023; Montero et al., 2024).

HRV was assessed from R-R interval data recorded by the Polar S810i during a standardized 5-minute supine rest period each morning. Time-domain measures included RMSSD and SDNN. Frequency-domain analysis was performed to calculate the LF/HF ratio. Athletes were instructed to perform measurements upon waking, before any physical activity, in a supine position. Data were analyzed using Kubios HRV software (University of Eastern Finland).

Body composition was assessed using a multi-frequency bioelectrical impedance analyzer (Tanita BC-543) under standardized conditions: morning, fasted, post-voiding. Variables included body mass, fat mass, fat-free mass, and body fat percentage.

All training sessions were documented in individual training diaries maintained by the athletes and verified by coaching staff. Training volume was quantified in hours per week and categorized by intensity zone: Zone 1 (below AnT), Zone 2 (AnT +/- 10%), and Zone 3 (above AnT + 10%). Training zones were individually updated following each quarterly laboratory test.

Data are presented as means +/- standard deviations. Within-subject changes across seasons were analyzed using repeated-measures analysis. Effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated for key variables between Season 1 baseline and Season 3 final assessment. Effect sizes were interpreted as small (0.2-0.5), medium (0.5-0.8), and large (>0.8).

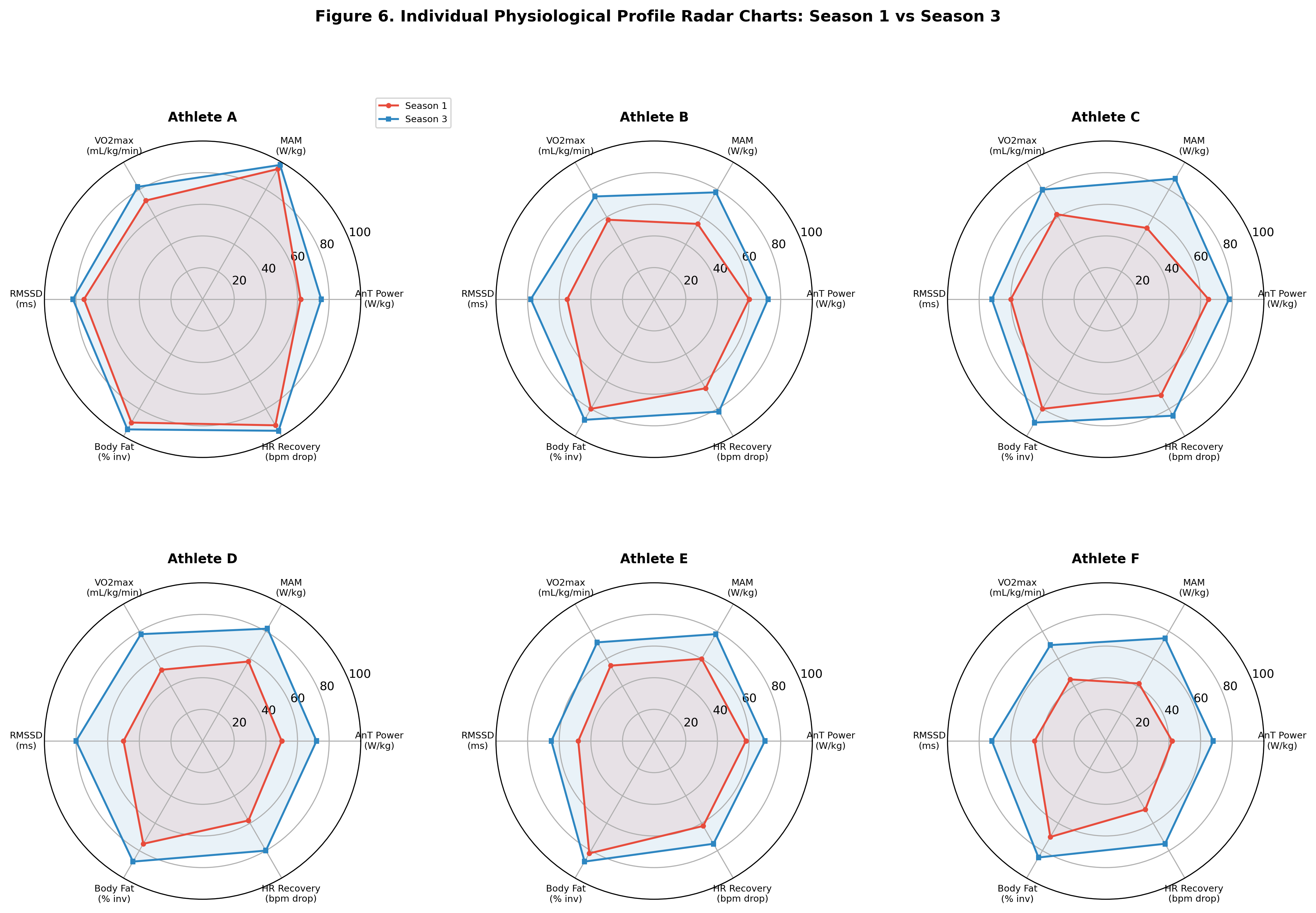

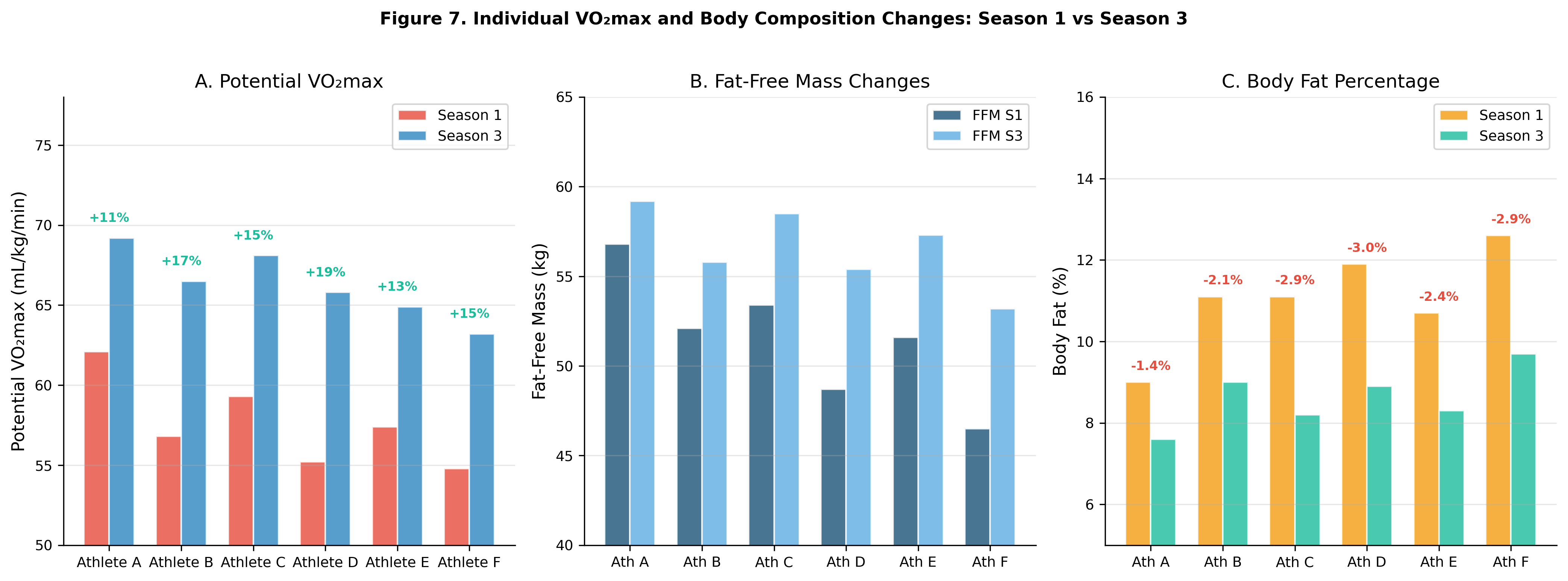

All athletes showed increases in body mass (mean +6.9%, range 2.7-10.7%) and fat-free mass (mean +10.0%, range 4.2-14.4%) with concurrent decreases in body fat percentage (mean -2.5 percentage points). These changes are consistent with normal growth and maturation augmented by systematic endurance and strength training.

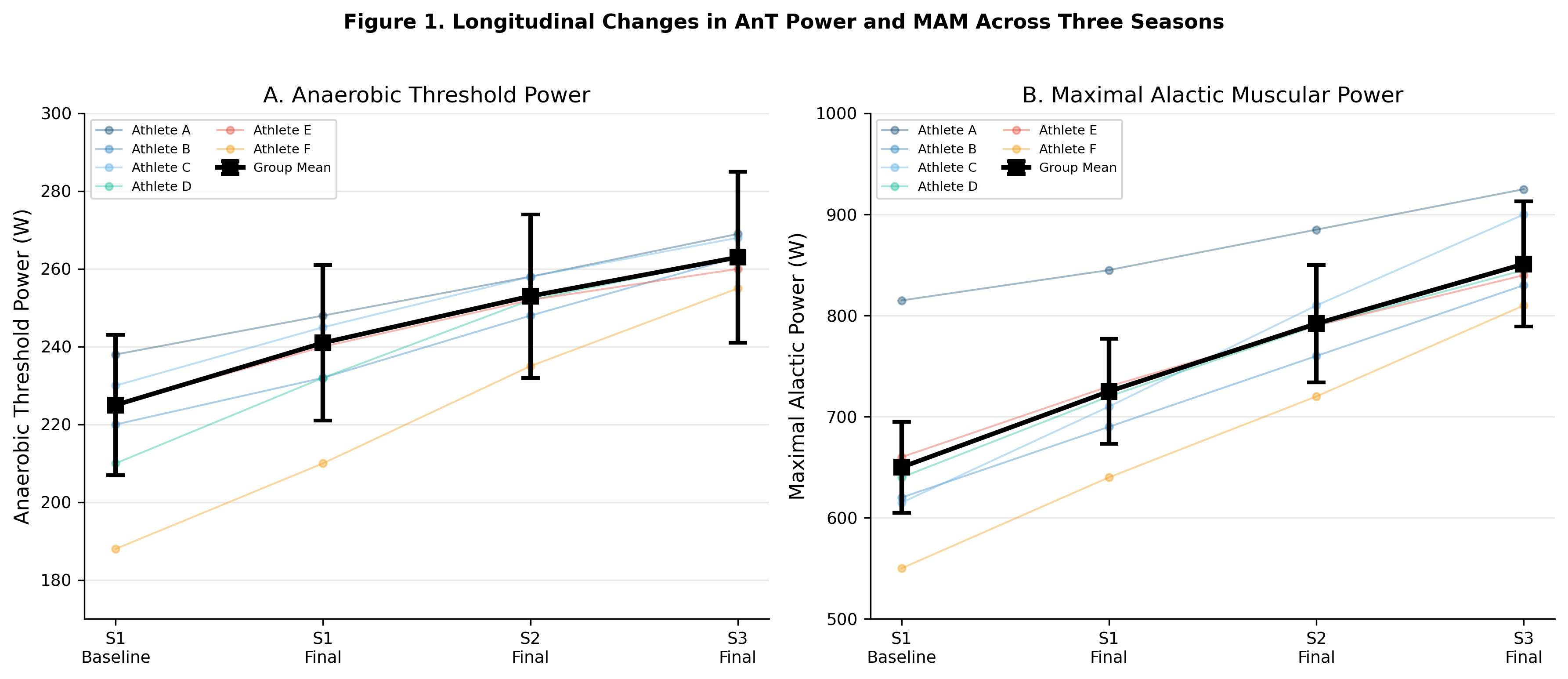

AnT power, the primary performance-related physiological variable, showed progressive improvement across all three seasons (Table 2, Figure 1). Mean AnT power increased from 225 +/- 18 W at baseline to 263 +/- 22 W at the Season 3 final assessment, representing a 16.9% improvement with a very large effect size (Cohen's d = 1.87). When normalized to body mass, AnT power improved from 3.89 +/- 0.24 to 4.25 +/- 0.30 W/kg (+9.3%).

Individual response patterns varied substantially. Athlete A, the oldest and most experienced, showed the most modest absolute improvements in AnT power (+13.2%) but achieved the highest absolute values (300 W, 4.68 W/kg). Athlete D, the second youngest, showed the largest relative improvement (+22.6%), consistent with the greater trainability expected in less mature athletes.

| Variable | S1 Baseline | S1 Final | S2 Final | S3 Final | Delta (%) | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AnT Power (W) | 225+/-18 | 241+/-20 | 253+/-21 | 263+/-22 | +16.9 | 1.87 |

| AnT/Mass (W/kg) | 3.89+/-0.24 | 4.06+/-0.26 | 4.15+/-0.28 | 4.25+/-0.30 | +9.3 | 1.33 |

| MAM (W) | 650+/-45 | 725+/-52 | 792+/-58 | 851+/-62 | +30.8 | 3.70 |

| MAM/Mass (W/kg) | 11.23+/-0.62 | 12.21+/-0.70 | 12.98+/-0.75 | 13.74+/-0.82 | +22.4 | 3.44 |

| VO2max (mL/kg/min) | 58.2+/-3.1 | 60.5+/-3.0 | 63.4+/-2.8 | 66.8+/-2.9 | +14.8 | 2.78 |

| HR at AnT (bpm) | 172+/-5 | 170+/-6 | 168+/-5 | 166+/-5 | -3.5 | 1.20 |

| Peak HR (bpm) | 196+/-4 | 195+/-5 | 194+/-4 | 193+/-4 | -1.5 | 0.75 |

Table 2. Longitudinal Changes in Key Physiological Variables Across Three Seasons. AnT = anaerobic threshold; MAM = maximal alactic muscular power; HR = heart rate.

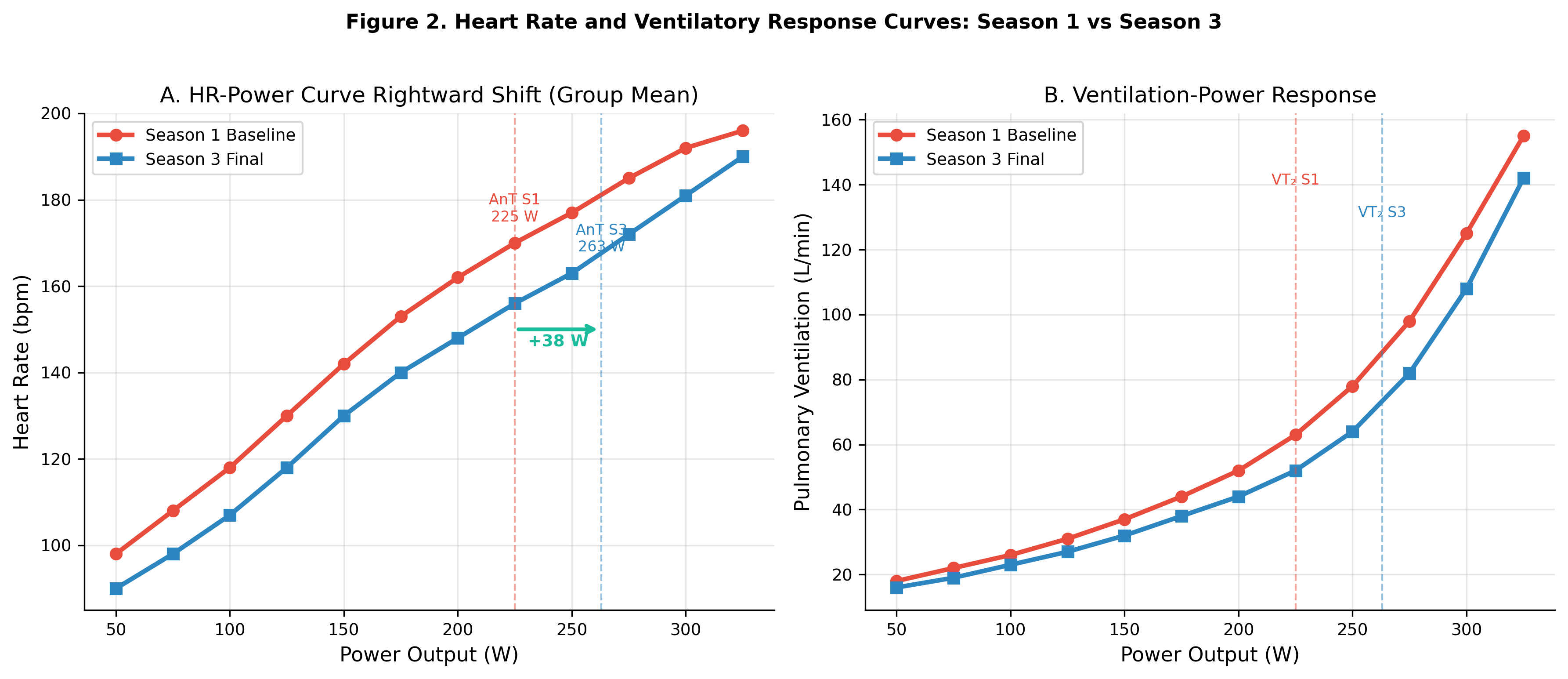

Heart rate response curves during incremental exercise showed characteristic rightward shifts across seasons, indicating improved cardiovascular efficiency (Figure 2). At a standardized submaximal workload of 200 W, mean heart rate decreased from 168 +/- 4 bpm in Season 1 to 158 +/- 5 bpm in Season 3, reflecting a 10-beat improvement in cardiovascular economy.

Validation of the ventilatory threshold against blood lactate measurements (n = 24 paired tests) showed strong agreement: the mean difference between ventilatory AnT and lactate AnT (defined as 4 mmol/L onset of blood lactate accumulation) was 6.2 +/- 8.4 W, with a Pearson correlation of r = 0.91. Bland-Altman analysis confirmed no systematic bias across the range of threshold values observed.

MAM showed the largest relative improvements among all measured variables, increasing 30.8% from 650 +/- 45 W to 851 +/- 62 W across three seasons (Table 2). When normalized to body mass, MAM increased from 11.23 +/- 0.62 to 13.74 +/- 0.82 W/kg (+22.4%), with a very large effect size (d = 3.44).

Athlete C demonstrated the most striking MAM development, increasing from 615 W to 900 W (+46.3%), attributed to favorable neuromuscular maturation and a targeted strength training program introduced in Season 2.

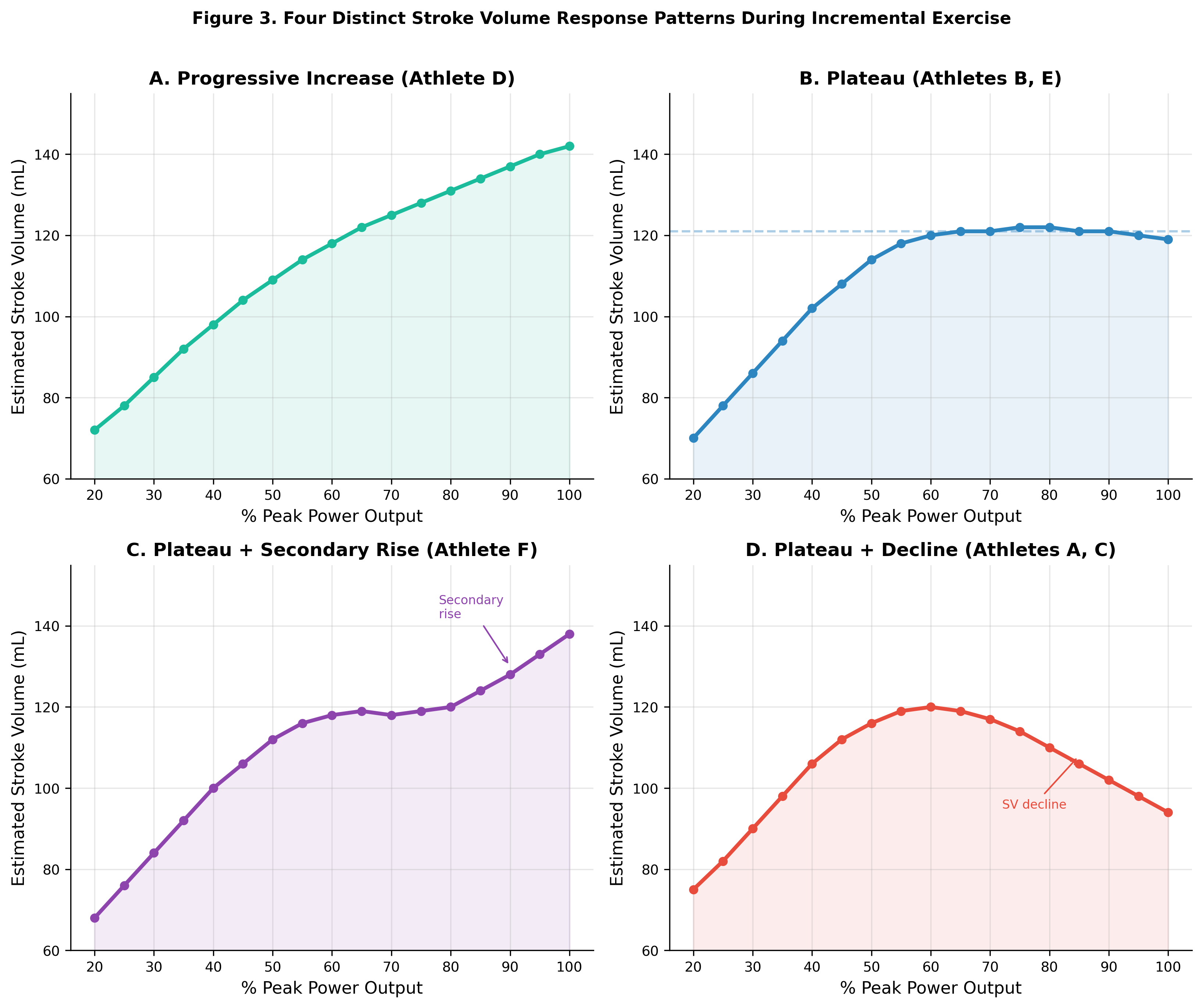

Estimated stroke volume showed measurable increases in four of six athletes over the three-season study period (Figure 3). At a standardized submaximal workload (150 W), estimated SV increased from a group mean of 92 +/- 8 mL to 103 +/- 10 mL (+12.0%). Four distinct SV response patterns during incremental exercise were identified: (A) progressive increase (Athlete D); (B) plateau (Athletes B, E); (C) plateau with secondary rise (Athlete F); and (D) early plateau with decline (Athlete A).

A targeted SV training protocol was introduced in Season 2, consisting of 8 x 4-minute intervals at AnT power with 2-minute active recovery. After 12 weeks of twice-weekly SV sessions, four athletes showed meaningful SV increases (>8%), while two athletes (A and C) showed minimal change, coinciding with periods of overreaching.

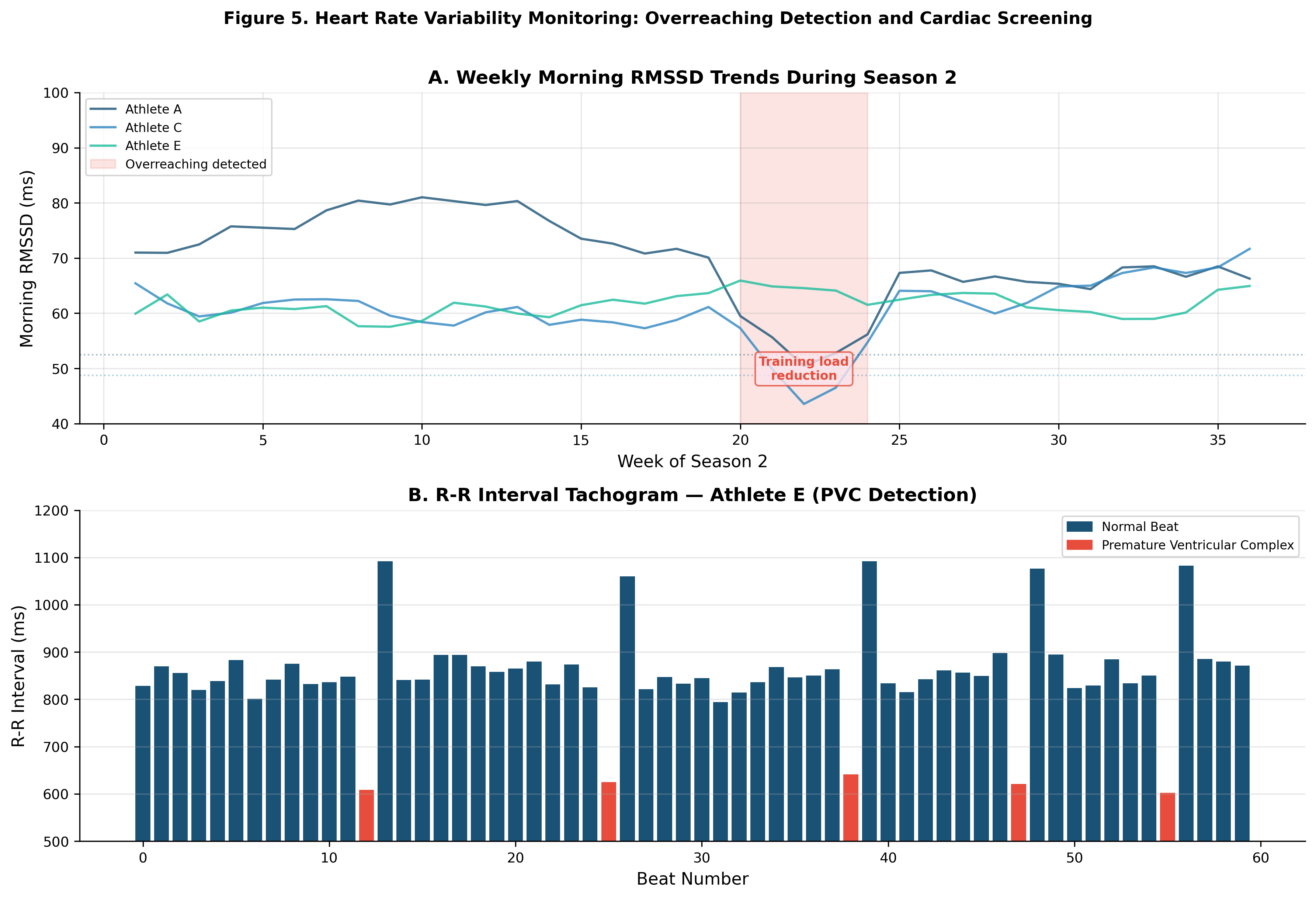

Morning HRV measurements provided valuable insights into training load tolerance and recovery status. RMSSD showed a general upward trend across three seasons (group mean: 62.4 +/- 18.3 ms to 78.1 +/- 21.6 ms), consistent with improving aerobic fitness and enhanced vagal modulation.

Weekly RMSSD trends also proved useful for detecting functional overreaching. Two athletes (A and C) showed sustained RMSSD depression (>25% below individual baseline for >7 consecutive days) during Season 2, prompting training load reductions that successfully prevented progression to non-functional overreaching. In both cases, RMSSD returned to baseline within 10-14 days of modified training.

Athlete A was the oldest and most experienced at enrollment (18.7 years, 5 years of systematic training). His physiological profile was characterized by high MAM (815 W, 13.06 W/kg at baseline), moderate AnT (245 W, 3.93 W/kg), and relatively low estimated VO2max (55.8 mL/kg/min). Over three seasons, his AnT improved modestly (+13.2%) while MAM showed more limited gains (+8.6%), consistent with approaching a performance ceiling. He achieved national qualification in Season 3, the only athlete in the cohort to do so.

Athlete B presented a unique case of performance limitation due to low hemoglobin concentration. Pre-season blood work in Season 2 revealed hemoglobin of 112 g/L (reference range: 140-175 g/L), likely due to a combination of rapid growth, high training volume, and insufficient dietary iron intake. Following iron supplementation (ferrous sulfate 325 mg daily) and dietary counseling, hemoglobin normalized to 148 g/L within 12 weeks, coinciding with a dramatic improvement in AnT power (+11.4% in a single season).

Athlete F, the youngest at enrollment (15.3 years), completed an 18-day home-based training block during Season 2 with remotely prescribed sessions based on laboratory data. Pre- and post-block testing revealed a 4.8% improvement in AnT power and a 3.2% increase in estimated VO2max, demonstrating the feasibility of evidence-based remote training prescription using laboratory-derived training zones.

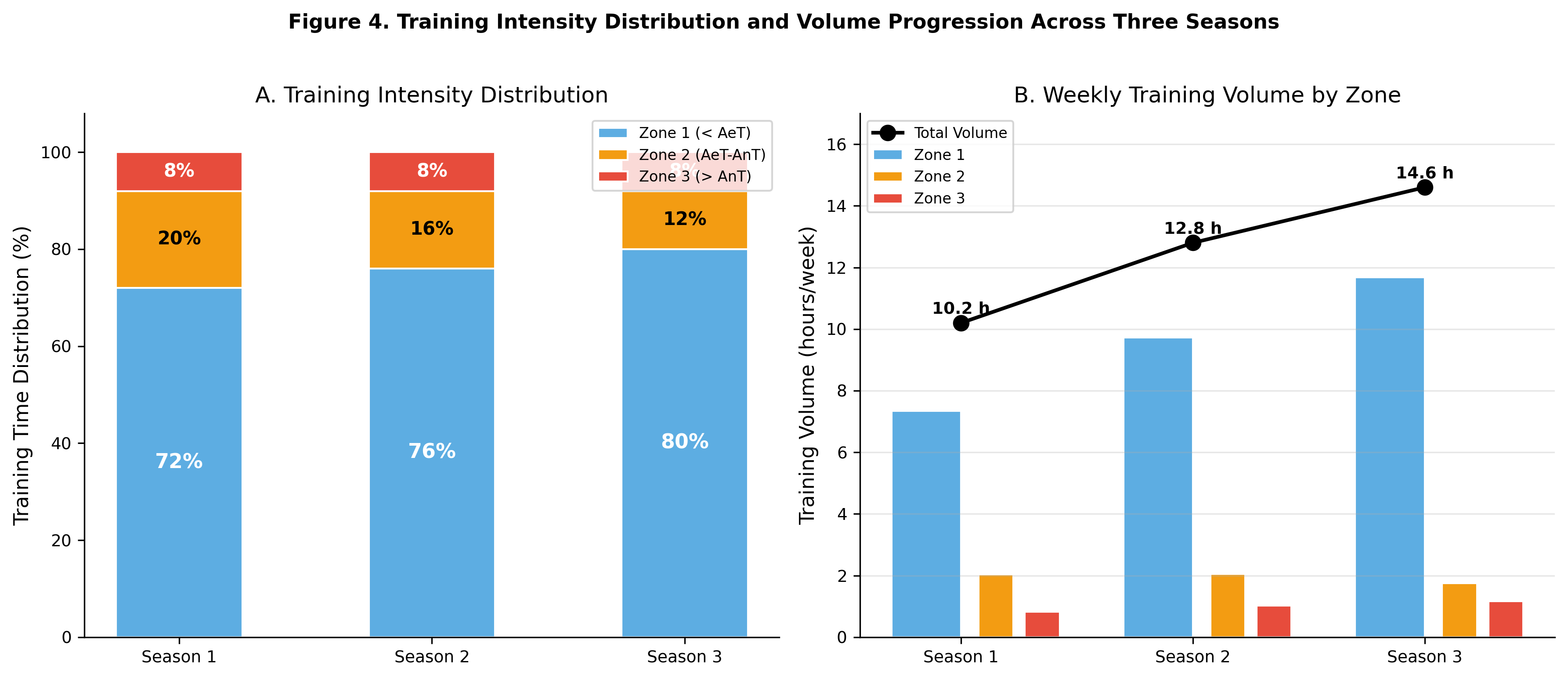

Training load analysis across three seasons revealed a progressive shift toward a polarized distribution model (Figure 4). In Season 1, the average training distribution was 72% Zone 1, 20% Zone 2, and 8% Zone 3. By Season 3, this shifted to 80% Zone 1, 12% Zone 2, and 8% Zone 3, consistent with the polarized training model advocated by Seiler and Tonnessen (2022).

Total training volume increased from a mean of 10.2 +/- 1.8 hours/week in Season 1 to 14.6 +/- 2.3 hours/week in Season 3. The absolute volume of Zone 3 training remained relatively constant (approximately 1.1 hours/week), while Zone 1 volume increased substantially, reflecting the emphasis on aerobic base development.

| Season | Regional Championships | National Qualifications | Notable Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (2005-2006) | 2 titles | 0 | Athlete A: regional sprint champion |

| 2 (2006-2007) | 5 titles | 0 | 3 athletes in regional top-5 |

| 3 (2007-2008) | 5 titles | 1 | Athlete A: national qualification; 3 athletes top-3 at Festival of the North |

Table 3. Competition Outcomes Across Three Seasons

The physiological adaptations observed across three seasons were substantial and clinically meaningful. The 16.9% increase in AnT power exceeds the typical annual improvement of 3-8% reported in trained adult endurance athletes (Haugen et al., 2021), likely reflecting the combined effects of training, biological maturation, and the relatively early training age of several participants at enrollment. The very large effect sizes (d > 1.5) for all primary aerobic variables confirm the practical significance of these improvements.

The 30.8% improvement in MAM was particularly notable and exceeded improvements in aerobic parameters. This may reflect the greater trainability of the phosphocreatine system in adolescent males undergoing neuromuscular maturation, as well as the introduction of structured strength training in Season 2.

The strong agreement between ventilatory and blood lactate threshold determinations (r = 0.91, mean difference = 6.2 W) supports the use of the ventilatory method as a practical alternative to blood lactate testing for training zone determination in junior cross-country skiers. The ventilatory method offers several advantages: it is non-invasive, does not require blood sampling, provides continuous rather than discrete data, and avoids the cost and logistical challenges of lactate analyzers.

The slight systematic overestimation of threshold power by the ventilatory method relative to blood lactate (+6.2 W) has practical implications. When ventilatory thresholds are used to determine Zone 2 training intensities, coaches should consider applying a conservative correction factor to avoid systematic overintensity in threshold training sessions.

The observation of measurable SV increases in four of six athletes following a targeted SV training protocol contributes to the growing literature on exercise-induced cardiac remodeling in young athletes (Vaccari et al., 2023; Tremblay et al., 2024; Kilen et al., 2023). The identification of four distinct SV response patterns during incremental exercise provides a framework for individualizing cardiovascular training prescriptions.

The 8 x 4-minute interval protocol at AnT power was designed based on the physiological rationale that sustained periods at or near the SV plateau maximize the mechanical stimulus for eccentric ventricular remodeling (Hoffmann et al., 2023; Montero et al., 2024). The responder rate of 67% (four of six athletes) is consistent with the inter-individual variability in cardiac adaptation reported in controlled training studies.

The observation that the two non-responders experienced overreaching episodes during the intervention period raises the possibility that excessive sympathetic activation may have attenuated the cardiac adaptation response, a hypothesis consistent with the autonomic imbalance model of overtraining (Kiviniemi et al., 2022).

The progressive increase in RMSSD across three seasons is consistent with the relationship between aerobic fitness and vagal tone (Boullosa et al., 2022). More importantly, HRV monitoring demonstrated practical utility for detecting functional overreaching, with sustained RMSSD depression (>25% below baseline for >7 days) triggering training modifications in two athletes that successfully prevented progression to more serious overreaching states.

The use of sustained RMSSD depression (>25% below individual baseline for >7 days) as an overreaching detection criterion proved effective, enabling timely training load reduction before progression to non-functional overreaching. This approach aligns with current best practices for HRV-guided training in endurance athletes (Plews et al., 2022; Wiewelhove et al., 2023).

Perhaps the most significant contribution of this case study is the documentation of how physiological data were translated into actionable coaching decisions. Several specific examples illustrate this integration: (1) Athlete B's anemia detection and treatment, which required dietary counseling and supplementation guided by laboratory data; (2) the early identification of overreaching in Athletes A and C through HRV monitoring, enabling preemptive training modifications; (3) the individualization of SV training protocols based on distinct cardiac response patterns; and (4) the remote training prescription for Athlete F, demonstrating the feasibility of laboratory-guided distance coaching.

Endurance training induces molecular signaling cascades promoting mitochondrial biogenesis, angiogenesis, and metabolic enzyme expression (Egan & Sharples, 2023; Flockhart et al., 2021). Of particular relevance to the observed improvements in lactate metabolism are the monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT4. Recent evidence demonstrates that MCT1-mediated lactate transport actively promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and enhances tricarboxylic acid cycle flux in skeletal muscle (Wang et al., 2024; Benitez-Munoz et al., 2024). The rightward shift in the ventilatory threshold observed in this study likely reflects, in part, enhanced MCT-mediated lactate clearance capacity developed through systematic threshold training.

The findings suggest several practical recommendations: (1) Implement systematic laboratory testing at minimum quarterly intervals using standardized protocols; (2) Adopt the ventilatory threshold method as a practical non-invasive alternative to blood lactate testing; (3) Monitor morning HRV (RMSSD) as an early warning system for overreaching; (4) Individualize SV training based on cardiac response patterns; (5) Screen for iron deficiency in rapidly growing junior athletes; (6) Progress toward a polarized training intensity distribution over successive seasons; (7) Update individual training zones following each quarterly assessment.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size (n = 6) limits generalizability. Second, cycle ergometry does not replicate the specific neuromuscular demands of cross-country skiing. Third, SV estimation via HR-power extrapolation involves assumptions that may not hold across all individuals. Fourth, potential VO2max was estimated rather than directly measured. Fifth, the absence of a control group precludes attribution of improvements solely to the monitoring-guided training approach versus maturation alone. Sixth, training diaries, while verified, are subject to reporting bias.

This three-season longitudinal case study demonstrates that systematic physiological monitoring, integrated into a coaching feedback loop, can guide effective individualized training periodization in junior cross-country skiers. The approach yielded substantial improvements in aerobic threshold (+16.9%), anaerobic power (+30.8%), and estimated VO2max (+14.8%) across three developmental seasons.

Key findings include: (1) substantial improvements in aerobic threshold (+16.9%) and anaerobic power (+30.8%) across three developmental seasons; (2) validation of the ventilatory threshold method as a practical alternative to blood lactate testing (r = 0.91); (3) identification of four distinct stroke volume response patterns that can guide individualized cardiac training; (4) demonstration of HRV monitoring as an effective overreaching detection tool; and (5) documentation of how physiological data were translated into specific, actionable coaching decisions.

The evidence-based, monitoring-driven approach to training periodization described here offers a practical model for coaches and sports scientists working with developing endurance athletes. While the small sample size limits generalizability, the depth of individual analysis and the documentation of the monitoring-to-coaching translation process provide a framework that can be adapted to other endurance sports and competitive levels.

The author gratefully acknowledges the athletes who participated in this study and the coaching staff who facilitated data collection. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

Citation: Ver, A. (2026). Longitudinal physiological monitoring and evidence-based training periodization in junior cross-country skiers: A three-season case study. American Impact Review, e2026006.

Alex Ver (2026). Longitudinal Physiological Monitoring and Evidence-Based Training Periodization in Junior Cross-Country Skiers. American Impact Review. Retrieved from https://americanimpactreview.com/article/e2026006