Genetic Markers for Talent Identification and Training Individualization in Elite Combat Sport and Endurance Athletes: Insights from a National Sports Science Program

Category: Health & Biotech

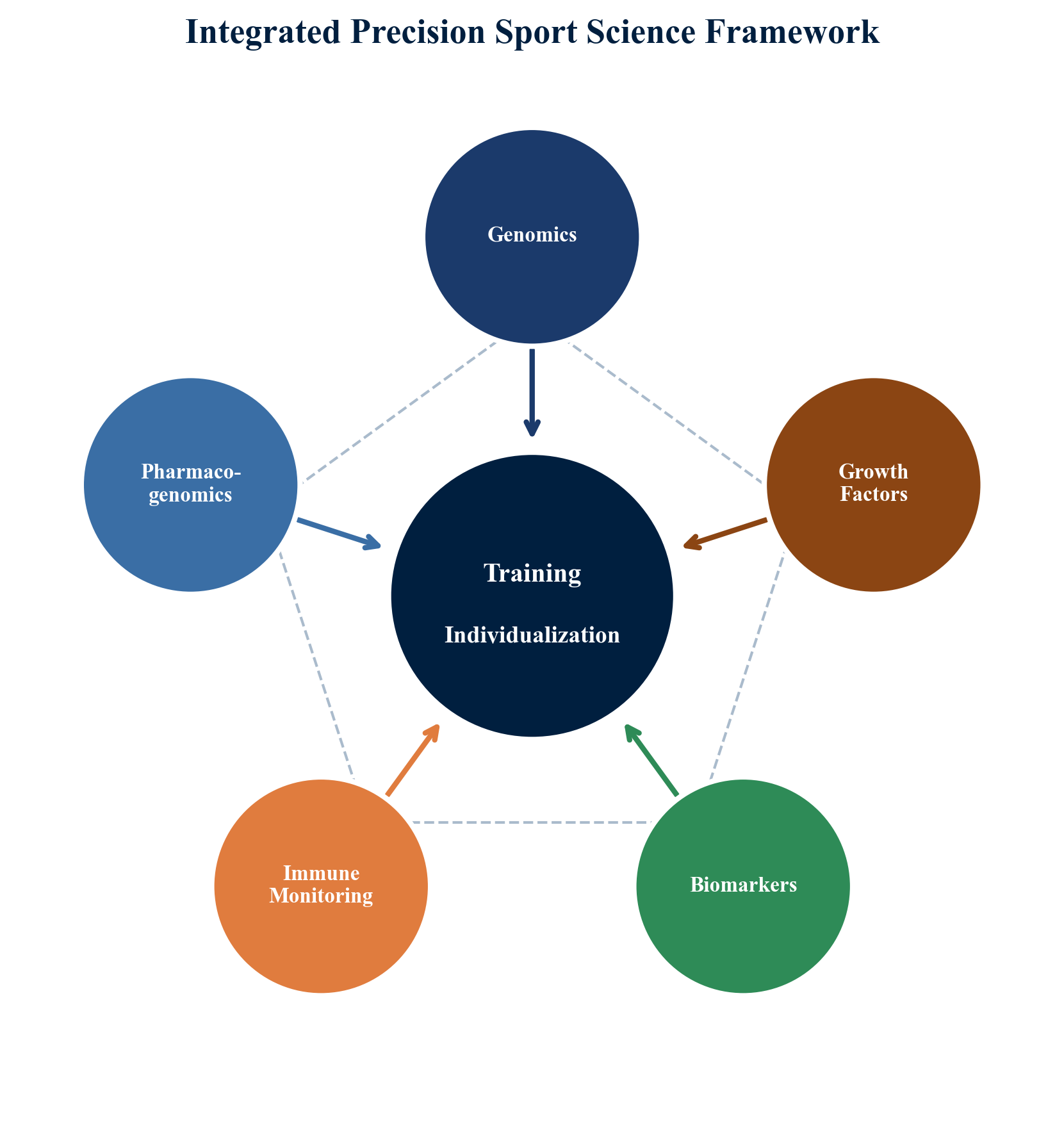

Background: The emergence of molecular biology tools in sport has ushered in an era of precision athlete management, in which genetic profiling, biomarker monitoring, and pharmacogenomic individualization promise to transform talent identification, training periodization, and injury prevention.

Purpose: This applied review synthesizes findings from a multi-year national sports science research program (2006-2009) involving 127 elite athletes from Greco-Roman wrestling, canoe/kayak sprint, rowing, and weightlifting, and contextualizes them within the current state of sports genomics, pharmacogenomics, and exercise immunology.

Methods: The program employed real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to genotype athletes for polymorphisms in ACE, AGT, ACTN3, AMPD1, MYH7, VDR, COL1A1, and CALCR genes. Pharmacogenetic profiles were constructed using DNA microchip technology targeting cytochrome P450 enzymes and glutathione S-transferases. Longitudinal immune monitoring included flow cytometric lymphocyte subset analysis, quantitative viral load assessment, and cytokine gene expression profiling.

Results: Mutations in AGT, AGT2R1, ACTN3, and AMPD1 were significantly associated with physical performance phenotypes. Pharmacogenetic profiling revealed inter-individual variation in response to whey colostrum and branched-chain amino acid supplementation based on CYP and GST genotypes. Immune monitoring documented training-load-dependent viral reactivation, NK cell suppression, and CD4/CD8 ratio inversion during intensive training mesocycles. Mechano growth factor (MGF) was detected exclusively in working and mechanically damaged muscle tissue.

Conclusions: The integration of genetic, immunological, pharmacogenomic, and biomarker data within a single national program demonstrates the feasibility and potential of precision sport science. While individual genetic variants explain only a small fraction of performance variance, multi-layered profiling approaches may enhance individualized training prescription and athlete health management.

Category: Health & Biotech

Elite sport performance is a complex, multifactorial phenotype shaped by the interplay of genetic predisposition, training history, nutritional status, psychological resilience, and environmental context. Over the past two decades, advances in molecular biology, bioinformatics, and wearable sensor technology have opened new frontiers in the scientific understanding of human athletic potential, catalyzing the emergence of what is now termed precision sport science.

The concept of precision sport science--analogous to precision medicine in clinical care--rests on the premise that athletes differ not only in their current fitness but in their genetic capacity to adapt to training stimuli, metabolize nutrients and supplements, mount and recover from immune challenges, and resist or recover from musculoskeletal injury. By characterizing these individual differences at the molecular level, practitioners aim to tailor training programs, nutritional strategies, recovery protocols, and injury prevention measures to the unique biological profile of each athlete.

Despite rapid growth in the scientific literature, most studies in sports genomics have been cross-sectional candidate-gene association studies, comparing allele frequencies between athlete and control populations. Few programs have attempted to integrate genetic, pharmacogenomic, immunological, and biomarker data within a single applied framework. This article reviews one such program--a multi-year national sports science initiative conducted between 2006 and 2009--and evaluates its findings against the current state of the field.

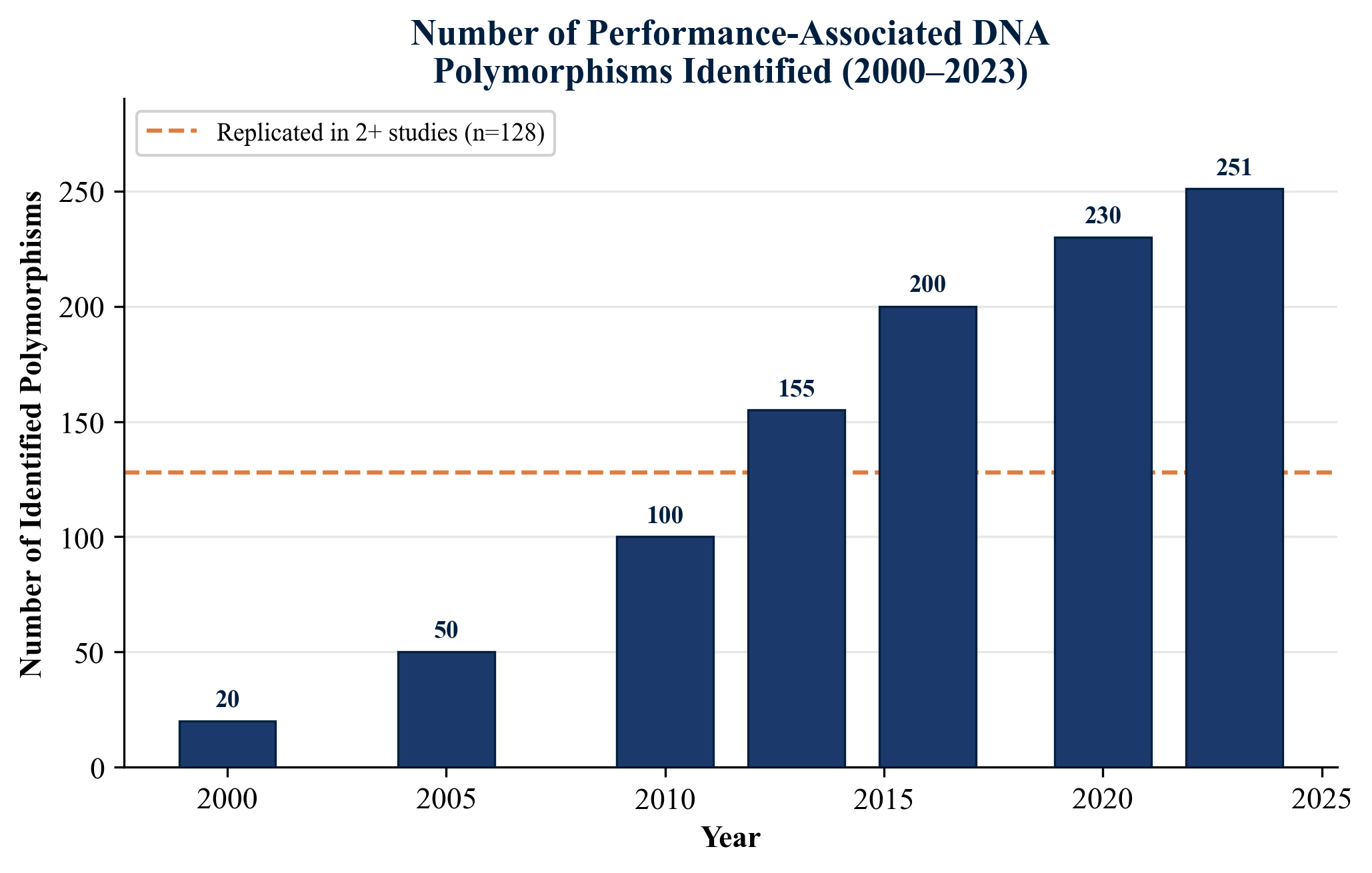

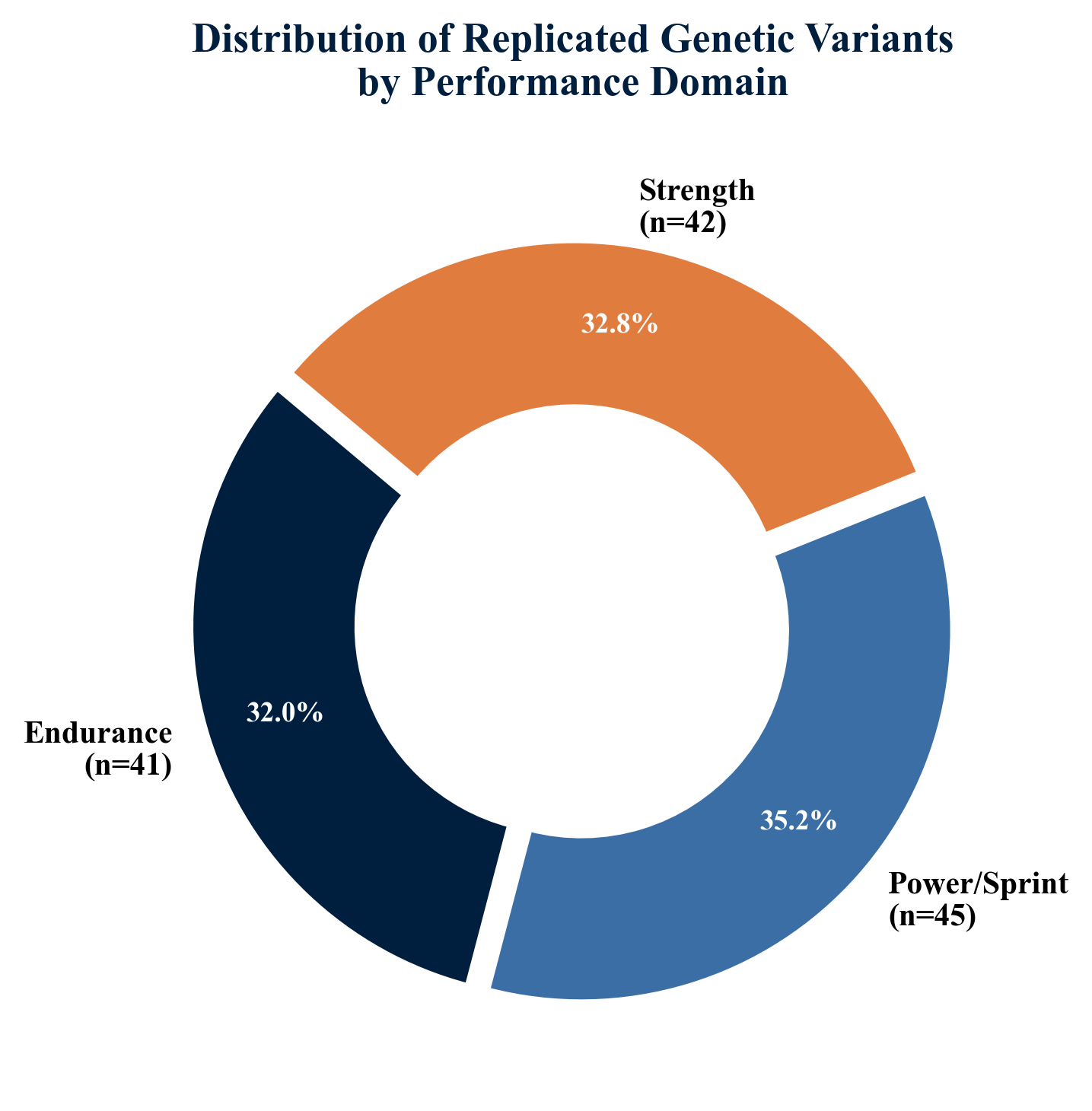

The search for genetic variants that predispose individuals to elite athletic performance has been one of the most active research frontiers in exercise science over the past two decades. As of 2023, more than 220 DNA polymorphisms have been associated with some aspect of physical performance, of which 128 have been replicated in at least two independent studies (Ahmetov et al., 2022). These variants span genes involved in skeletal muscle structure, energy metabolism, cardiovascular adaptation, oxygen transport, pain sensitivity, and injury susceptibility.

The ACTN3 gene encodes alpha-actinin-3, a structural protein expressed exclusively in type II (fast-twitch) muscle fibers. The R577X polymorphism (rs1815739) results in either a functional protein (R allele) or complete deficiency (X allele, homozygous XX). A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis of 178 studies confirmed that the ACTN3 RR genotype is significantly overrepresented in power and sprint athletes, while the XX genotype is more common among endurance athletes (Semenova et al., 2024). In Japanese elite athletes, Kumagai et al. (2022) further demonstrated sport-specific genotype distributions, with the R allele frequency highest in sprinters and lowest in long-distance runners.

Pickering and Kiely (2017) expanded the understanding of ACTN3 beyond speed, demonstrating that the polymorphism influences exercise recovery kinetics, susceptibility to exercise-induced muscle damage, and even bone mineral density. A 2023 systematic review confirmed that ACTN3 XX homozygotes are at elevated risk of non-contact soft tissue injuries, particularly anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures (Couto et al., 2023).

The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) gene insertion/deletion (I/D) polymorphism (rs4646994) has been one of the most extensively studied variants in exercise genomics since the original report by Montgomery et al. (1998). The I allele, associated with lower circulating ACE activity, has been linked to endurance performance, while the D allele, associated with higher ACE activity and greater angiotensin II-mediated vasoconstriction and muscle hypertrophy, has been linked to power and strength phenotypes.

A comprehensive 2024 meta-analysis of 16 studies confirmed a significant association between the ACE II and ID genotypes and elite endurance athlete status compared with the DD genotype (OR = 1.88, 95% CI: 1.51-2.34). However, no significant association was found for power athletes, suggesting the relationship is domain-specific (Pereira et al., 2024).

The angiotensinogen (AGT) gene M235T polymorphism (rs699) occupies a complementary position within the renin-angiotensin system. The C allele (235T) correlates with higher angiotensin II levels and has been associated with power sport performance (Zarebska et al., 2013; Gomez-Gallego et al., 2009). Additionally, the T allele has been linked to left ventricular hypertrophy in endurance athletes, suggesting a role in cardiac adaptation to exercise (Karjalainen et al., 1999).

The adenosine monophosphate deaminase 1 (AMPD1) gene encodes a skeletal muscle-specific enzyme critical to purine nucleotide cycle function during high-intensity exercise. The c.34C>T (rs17602729) nonsense variant leads to enzyme deficiency, and homozygous TT carriers experience exercise-induced myopathy and premature fatigue. A landmark 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis confirmed significant associations between AMPD1 CC genotype and both endurance (OR = 1.72) and power (OR = 2.17) athlete status (Rubio et al., 2025). Earlier work in Lithuanian athletes demonstrated that the CC genotype was associated with higher peak anaerobic power during the Wingate test (Gineviciene et al., 2014).

Beyond the canonical performance-associated variants, several genes relevant to musculoskeletal integrity have emerged as important for athlete profiling. The COL1A1 Sp1 binding site polymorphism (rs1800012) has been linked to ACL rupture risk and soft tissue injury susceptibility in professional soccer players (Ficek et al., 2013; Pruna et al., 2013). VDR (vitamin D receptor) gene polymorphisms influence bone mineral density, serum vitamin D levels, and stress fracture risk, with recent data from elite athletes in Kazakhstan confirming associations with injury predisposition (Yessenbekova et al., 2025). The CALCR (calcitonin receptor) gene participates in calcium homeostasis and bone remodeling pathways relevant to stress fracture prevention.

A persistent challenge in sports genomics is the small individual effect size of any single polymorphism. Ahmetov et al. (2022) emphasized that no single genetic variant accounts for more than a marginal fraction of the variance in any performance trait. Early attempts to construct total genotype scores (TGS) combining multiple variants yielded modest predictive power, with Santiago et al. (2010) reporting that world-class endurance athletes carried a higher proportion of "endurance-favorable" alleles across a panel of seven polymorphisms. Ruiz et al. (2009) similarly explored a power-oriented polygenic profile, finding significant but modest separation between elite power athletes and controls. The fundamental challenge remains the polygenicity of athletic performance, compounded by gene-environment interactions, epigenetic regulation (Seaborne et al., 2018), and the influence of training history on gene expression.

| Gene | Polymorphism | Associated Phenotype | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACTN3 | R577X (rs1815739) | Power/sprint performance; injury risk | RR genotype overrepresented in power athletes; XX linked to higher non-contact injury risk |

| ACE | I/D (rs4646994) | Endurance vs. power performance | I allele associated with endurance (OR = 1.88 for II/ID vs. DD); no association with power |

| AGT | M235T (rs699) | Power performance; cardiac remodeling | C allele (235T) linked to power sports; T allele to LV hypertrophy in endurance athletes |

| AMPD1 | c.34C>T (rs17602729) | Endurance and power performance | CC genotype overrepresented in athletes (OR = 1.72 endurance, 2.17 power) |

| COL1A1 | Sp1 (rs1800012) | ACL rupture; tendon injury | TT genotype protective against ligament/tendon injuries in soccer players |

| VDR | TaqI polymorphism | Bone density; vitamin D status | Linked to vitamin D insufficiency and elevated injury rates in elite athletes |

| CALCR | Various | Calcium homeostasis; stress fracture | Participates in bone remodeling pathways relevant to stress fracture risk |

| MYH7 | Various | Cardiac muscle function | Cardiac myosin heavy chain; relevant to cardiac adaptation in endurance training |

Table 1. Key Genetic Polymorphisms Assessed in the National Sports Science Program

Pharmacogenomics--the study of how genetic variation influences drug and supplement metabolism--represents an underexplored but potentially transformative frontier in athlete management. The cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzyme superfamily, which metabolizes the majority of xenobiotics including drugs, supplements, and dietary compounds, exhibits extensive genetic polymorphism that produces a spectrum of metabolizer phenotypes from ultra-rapid to poor.

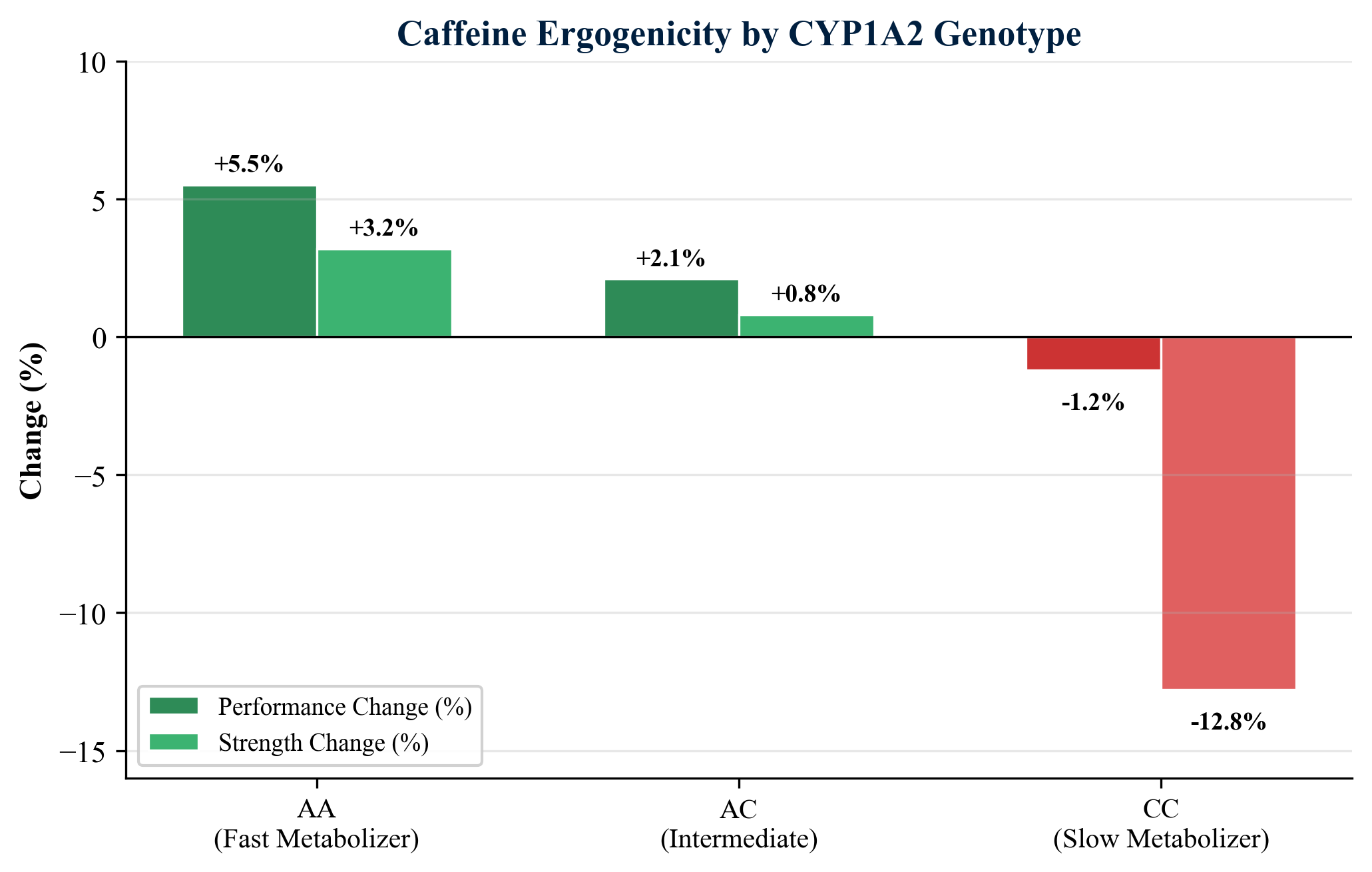

Perhaps the most well-characterized pharmacogenomic interaction in sport concerns the CYP1A2 -163C>A polymorphism (rs762551) and caffeine metabolism. Individuals with the AA genotype (fast metabolizers) demonstrate consistent ergogenic benefits from caffeine, including improved endurance performance and time-trial results (Guest et al., 2018). In contrast, CC genotype carriers (slow metabolizers) may experience detrimental effects, with Rahimi (2021) documenting a 12.8% decrease in handgrip strength following caffeine ingestion in CC carriers compared to placebo. A 2021 systematic review confirmed genotype-dependent effects on exercise performance, with AA carriers showing the most robust positive responses (Grgic et al., 2021). Pickering and Kiely (2019) argued that current blanket caffeine recommendations in sport are suboptimal and should be individualized based on CYP1A2 genotype.

The glutathione S-transferase (GST) enzyme family plays a critical role in the detoxification of reactive oxygen species generated during intense exercise. Individuals with GSTM1 or GSTT1 null genotypes (homozygous gene deletion) lack functional enzyme activity and demonstrate impaired antioxidant capacity. A 2020 meta-analysis confirmed that GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes are associated with greater exercise-induced oxidative damage (Ben Ayed et al., 2020). Kim et al. (2018) extended these findings to the Korean population, reporting associations between GST null genotypes and reduced aerobic performance.

Beyond caffeine and antioxidants, pharmacogenomic profiling has implications for the metabolism of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are widely used in sport for pain management, and for the optimization of supplement protocols including branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and protein concentrates.

| Gene/Enzyme | Polymorphism | Metabolizer Status | Implication for Athletes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP1A2 | -163C>A (rs762551) | AA = fast; AC = intermediate; CC = slow | Fast metabolizers benefit from caffeine; slow metabolizers may experience -12.8% strength loss |

| CYP2D6 | Multiple alleles | Ultra-rapid to poor metabolizer | Affects NSAID metabolism and analgesic efficacy; relevant to pain management protocols |

| CYP2C9 | Multiple alleles | Normal to poor metabolizer | Influences metabolism of anti-inflammatory agents and some supplements |

| CYP2C19 | Multiple alleles | Ultra-rapid to poor metabolizer | Affects proton pump inhibitor and supplement metabolism |

| GSTM1 | Null/Present | Null = absent enzyme activity | Null genotype associated with impaired antioxidant capacity and reduced aerobic performance |

| GSTT1 | Null/Present | Null = absent enzyme activity | Null genotype linked to greater exercise-induced oxidative damage |

| GSTP1 | Ile105Val | Variable enzyme activity | Modulates detoxification of exercise-generated reactive oxygen species |

Table 2. Pharmacogenomic Markers Assessed in the National Canoe/Kayak Sprint Team

The relationship between intensive training and immune function has been a subject of sustained scientific inquiry since Nieman's (1994) seminal articulation of the "open window" hypothesis, which proposed that prolonged, intense exercise creates a transient period of immunodepression during which athletes are more susceptible to opportunistic infections, particularly upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs).

The consensus position statement by Walsh et al. (2011) established that both innate and acquired immunity are transiently depressed in the hours following heavy exertion, with functional decrements reported in natural killer (NK) cell cytotoxicity, neutrophil oxidative burst capacity, salivary immunoglobulin A (sIgA) secretion rate, and T cell proliferative responses. Campbell and Turner (2018) challenged the simplistic "open window" model, arguing that immune cell redistribution--rather than true immunosuppression--accounts for many observed changes, but acknowledged that cumulative training stress, inadequate recovery, and psychosocial factors can produce clinically meaningful immunodepression.

Latent herpesvirus reactivation has emerged as a sensitive marker of immunological stress in athletes. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA shedding in saliva increases during periods of intensive training and competition, and elevated EBV viral load has been associated with increased URTI incidence in elite swimmers (Gleeson et al., 2002), professional footballers (He et al., 2021), and mixed-sport cohorts (Soares et al., 2021). Torque teno virus (TTV) and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) have also been proposed as complementary markers of immune status in athletes (Gleeson & Pyne, 2016).

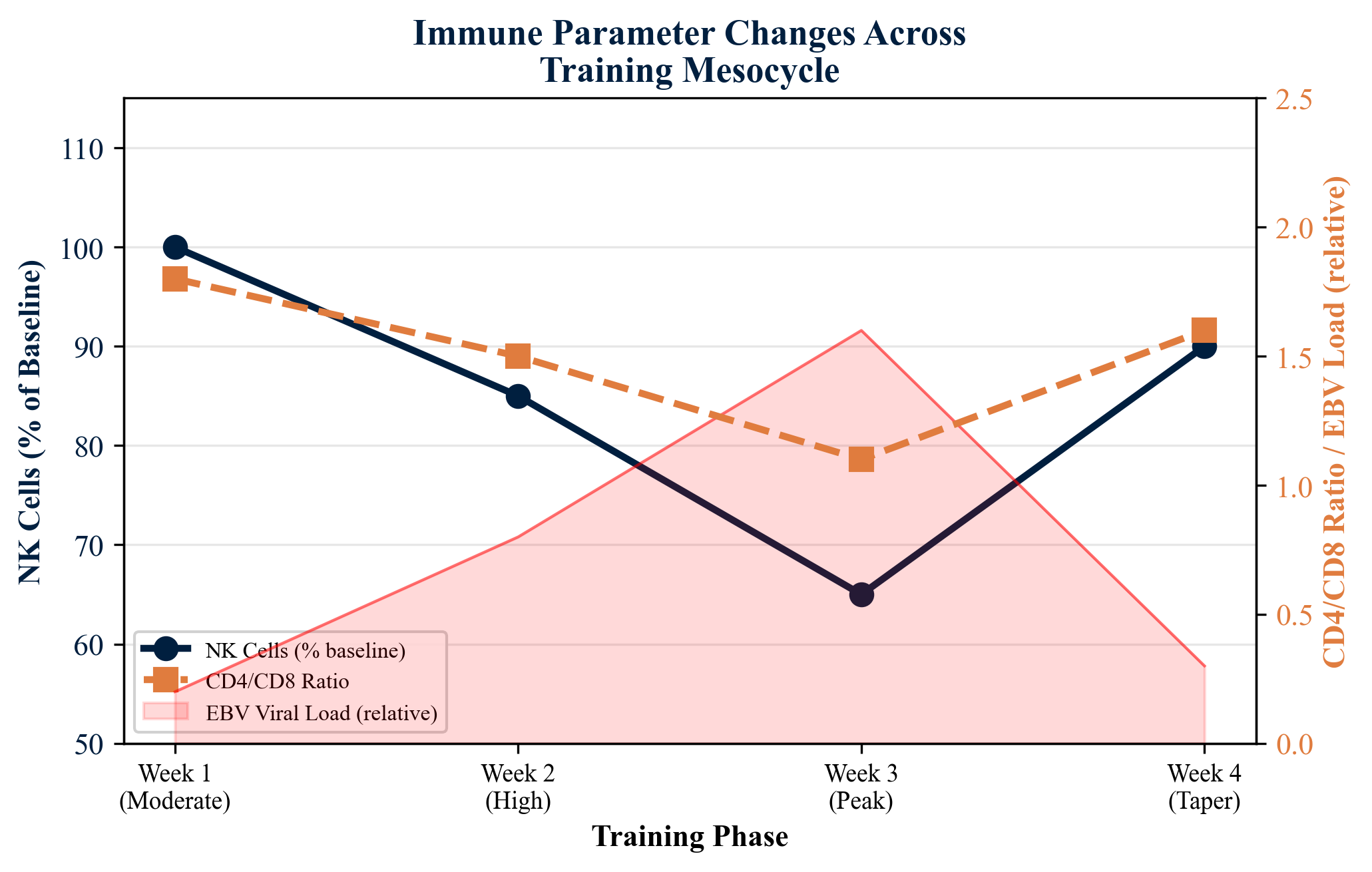

Flow cytometric enumeration of lymphocyte subsets--CD3+ T cells, CD4+ helper T cells, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, CD19+ B cells, and CD3-CD16+CD56+ natural killer (NK) cells--provides a detailed immunological profile that can be tracked longitudinally across training cycles. Sustained depression of NK cell counts and inversion of the CD4/CD8 ratio have been proposed as indicators of overreaching and immunological compromise.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), and interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) are key cytokines mediating the acute-phase response to exercise. IL-6, released from contracting skeletal muscle, functions as both a pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediator depending on context (Pedersen & Febbraio, 2008). Monitoring cytokine gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) provides insight into the systemic inflammatory balance during training.

| Parameter | Method | Training Phase Response | Recovery Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| NK Cells (CD3-CD16+CD56+) | Flow cytometry | Progressive decline during peak training volume (up to 35% below baseline) | Recovery toward baseline values during taper period |

| CD4/CD8 Ratio | Flow cytometry | Ratio inversion during most intensive training weeks | Gradual normalization during recovery/taper weeks |

| EBV Viral Load | Quantitative real-time PCR | Significant increase during peak training (up to 8-fold) | Rapid decline during taper; return to baseline within 7-10 days |

| TTV/HHV-6 Viral Load | Quantitative real-time PCR | Moderate increase during intensive training blocks | Variable recovery; HHV-6 may persist at elevated levels longer than EBV |

| IL-6 Expression | qPCR on PBMCs | Acute elevation post-exercise; cumulative suppression with overreaching | Returns to baseline with adequate recovery (48-72 h) |

| TNF-alpha Expression | qPCR on PBMCs | Suppressed during heavy training blocks | Recovery parallels overall immune reconstitution |

| IFN-gamma Expression | qPCR on PBMCs | Reduced during periods of intensive training | Slower recovery compared to IL-6; sensitive marker of immunodepression |

| Salivary IgA | ELISA | Decreased secretion rate during high-volume training | Recovery within 2-4 weeks of reduced training load |

Table 3. Immune Monitoring Parameters Assessed During Training Mesocycle Studies

Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) is a central mediator of skeletal muscle hypertrophy, acting through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway to promote protein synthesis and satellite cell activation (Schiaffino et al., 2013). Exercise-induced increases in both systemic and local IGF-1 concentrations have been well documented, with the magnitude and time course of response dependent on exercise modality, intensity, and nutritional status (Nindl et al., 2011).

Mechano growth factor (MGF) is a splice variant of the IGF-1 gene (IGF-IEb in rodents, IGF-IEc in humans) that is expressed specifically in mechanically loaded and damaged skeletal muscle tissue (Goldspink, 2005). MGF acts as an autocrine/paracrine factor promoting satellite cell activation and myoblast proliferation at the site of damage (Hill & Goldspink, 2003). Its detection in muscle biopsies provides direct evidence of local anabolic signaling in response to training.

Myostatin (encoded by the MSTN gene) functions as a negative regulator of muscle mass. Polymorphisms in MSTN, particularly rs1805086 (K153R), have been associated with muscle hypertrophy phenotypes in multiple populations (Kruszewski & Aksenov, 2022; Thomis et al., 2023). The balance between anabolic (IGF-1/MGF) and catabolic (myostatin) signaling determines the net hypertrophic response to resistance training.

The analysis of exhaled breath condensate (EBC) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) represents a genuinely non-invasive approach to physiological monitoring. Lactate concentration in EBC has been shown to correlate with blood lactate during incremental exercise, enabling non-invasive estimation of anaerobic threshold (Meyer et al., 2011; Hintze et al., 2022). King et al. (2018) demonstrated that dynamic VOC profiles change predictably with exercise intensity and metabolic stress.

The convergence of microfluidics, flexible electronics, and wireless communication has produced a new generation of wearable biosensors capable of continuous, non-invasive monitoring of sweat biomarkers including electrolytes, metabolites, and hormones (Gao et al., 2016; Seshadri et al., 2019). These devices offer the potential for real-time physiological monitoring during training and competition.

Stabilometric assessment of postural control and isokinetic dynamometry for muscle strength evaluation remain gold-standard biomechanical tools in athlete profiling. Modern force-plate systems with enhanced sensor arrays enable the assessment of rate of force development (RFD), an important determinant of explosive performance in combat sports and sprinting (Maffiuletti et al., 2019).

Gene doping--the non-therapeutic use of gene therapy technologies to enhance athletic performance--has been recognized as a threat by WADA since 2003, when it was first included in the Prohibited List. Potential targets include genes encoding erythropoietin (EPO), growth hormone (GH), insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), among others (Baoutina et al., 2008).

Early detection approaches leveraged the principle that transgene constructs, being derived from complementary DNA (cDNA), lack intronic sequences present in the native genomic gene. Real-time PCR targeting exon-exon junctions can therefore distinguish transgene-derived mRNA or DNA from endogenous gene expression (Beiter et al., 2011).

Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) assays have been developed for simultaneous detection of all exon-exon junctions across multiple potential doping genes--including EPO, IGF1, IGF2, GH1, and GH2--with sensitivity sufficient to detect low-level transgene DNA against a background of genomic DNA (Salamin et al., 2019; Li et al., 2024).

Hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers (HBOCs), which are included on the WADA Prohibited List, can be detected through electrophoretic screening methods that distinguish modified hemoglobin molecules from native hemoglobin variants (Leuenberger et al., 2004; Varlet-Marie et al., 2006).

Express methods for detecting 17-alkyl-substituted anabolic steroids--including methandienone, stanozolol, and oxandrolone--have evolved from immunoassay-based screening to high-resolution mass spectrometric methods capable of detecting trace metabolites in urine samples at sub-nanogram concentrations (Thevis & Schanzer, 2010).

Between 2006 and 2009, a national sports science institute conducted a multi-year applied research program integrating molecular biology, immunology, pharmacogenomics, biomechanics, and anti-doping science across four Olympic sport disciplines: Greco-Roman wrestling (n = 38), canoe/kayak sprint (n = 31), rowing (n = 29), and weightlifting (n = 29). The total cohort comprised 127 elite athletes competing at national and international levels. The program's distinguishing feature was its interdisciplinary integration, housing all research domains within a single institutional framework.

A universal real-time PCR (qPCR) format was developed, capable of detecting both single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and insertion/deletion polymorphisms within a single analytical platform. Athletes from all four disciplines were genotyped for polymorphisms in eight genes: ACE (I/D), AGT (M235T), ACTN3 (R577X), AMPD1 (c.34C>T), MYH7, VDR, COL1A1 (Sp1), and CALCR. Genotype data were correlated with laboratory and field performance measures specific to each sport.

Statistical analysis of genotype distributions revealed significant associations between mutations in AGT, AGT2R1, ACTN3, and AMPD1 and physical performance metrics. Specifically, power-oriented athletes (wrestlers, weightlifters) showed distinct genotype distributions compared to endurance-oriented athletes (rowers, kayakers), consistent with the current understanding of these polymorphisms' functional effects.

Cytochrome P450 family enzymes (including CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP2C9, and CYP2C19) and glutathione S-transferases (GSTM1, GSTT1, GSTP1) were genotyped in the national canoe/kayak sprint team to create individualized pharmacogenetic profiles. These profiles were used to predict inter-individual differences in the metabolism of nutritional supplements and to guide personalized supplementation protocols.

When standardized supplementation protocols involving whey colostrum and branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) were administered, significant inter-individual differences in physiological response were observed that correlated with CYP and GST genotype categories. This finding supported the concept of pharmacogenomically guided supplementation in sport.

Gene expression levels of IL-6, TNF-alpha, and IFN-gamma in peripheral blood mononuclear cells were quantified longitudinally across training mesocycles. Concurrently, viral loads for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), torque teno virus (TTV), and human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) were monitored using quantitative real-time PCR. Correlations between training load, cytokine expression, and viral reactivation were analyzed to identify immunological risk thresholds.

A detailed four-week training mesocycle study in national-team rowers employed flow cytometry to track lymphocyte subset dynamics. CD3+, CD4+, CD8+, CD19+, and CD3-CD16+CD56+ NK cell populations were enumerated at weekly intervals. Results confirmed a progressive decline in NK cell counts during high-volume training phases, with recovery during taper periods, and documented CD4/CD8 ratio inversion coinciding with periods of peak training stress.

An affinity isolation method was developed for separating growth hormone (GH) isoforms from human serum, enabling more precise characterization of the GH isoform profile under different training and recovery conditions. IGF-1 levels were correlated with training periodization variables and performance outcomes.

A significant finding concerned mechano growth factor (MGF), the IGF-IEc splice variant. MGF was detected exclusively in biopsies of working and mechanically damaged muscle tissue, not in resting or undamaged muscle. Furthermore, MGF selectively promoted proliferation of myoblasts rather than fibroblasts, supporting its role as a specific autocrine signal for muscle regeneration.

Stabilometric platforms and isokinetic dynamometers were used to assess sensorimotor function across all four sport disciplines. Universal assessment scales were developed to enable cross-sport comparison of postural control, rate of force development, and muscle balance ratios. These biomechanical profiles complemented the molecular and immunological data.

A novel spectrophotometric method for analyzing exhaled air, saliva, and skin surface emissions was developed and validated against established laboratory biomarkers. Protocols were created for assessing aerobic and anaerobic threshold using exhaled breath condensate, providing a non-invasive alternative to blood lactate testing.

Three anti-doping methodologies were developed during the program:

These methods were designed to complement existing WADA-accredited laboratory procedures and to provide national anti-doping authorities with additional rapid-screening capabilities.

The findings of the national program are broadly consistent with the subsequent decade of sports genomics research. The association of AGT, ACTN3, and AMPD1 polymorphisms with performance phenotypes has been confirmed by multiple independent meta-analyses (Ahmetov et al., 2022; Semenova et al., 2024; Rubio et al., 2025). The differentiation between power- and endurance-associated genotype profiles aligns with the understanding that these represent partially distinct genetic architectures.

The pharmacogenomic component of the program was notably ahead of its time. While clinical pharmacogenomics has become standard practice in oncology and cardiology, its systematic application in sport remains in its infancy. The demonstration that CYP and GST genotypes predicted differential responses to supplementation presaged the current movement toward personalized sports nutrition.

The immune monitoring data, documenting correlations between training load and viral reactivation in a controlled mesocycle design, resonate with the growing body of evidence that latent herpesvirus dynamics serve as sensitive biomarkers of immunological stress in athletes.

The program's principal strength lay in its integrative design: by housing genetic, pharmacogenomic, immunological, endocrinological, biomechanical, biomarker, and anti-doping research within a single institutional framework, it enabled cross-domain analysis that is rarely possible in university-based or single-laboratory research settings.

Several limitations merit acknowledgment. The sample size of 127 athletes, while substantial for an elite-athlete study, limits statistical power for detecting small-to-moderate genetic effects, particularly when stratified by sport or event. The candidate-gene approach, while appropriate for the technological capabilities of the era, captures only a fraction of the genetic architecture underlying athletic performance.

The 15 years since the program's conclusion have witnessed transformative advances in sports genomics methodology. Whole-genome sequencing has become economically feasible, enabling the detection of rare variants and structural variants not captured by candidate-gene approaches. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been applied to exercise-related traits, though statistical power remains a challenge due to the difficulty of assembling sufficiently large cohorts of elite athletes (Pitsiladis et al., 2016; Bouchard et al., 2011). The emergence of epigenomics--particularly the discovery that skeletal muscle retains an epigenetic memory of prior hypertrophy (Seaborne et al., 2018)--has added a new dimension to the understanding of training adaptation that was not accessible to the original program.

In anti-doping science, the approval of the first gene doping test by WADA in 2021, followed by the development of CRISPR-Cas12a-based multiplexed detection platforms (Bao et al., 2025), represents a vindication of the program's early investment in PCR-based transgene detection.

The findings of the national program, contextualized within the current literature, yield several actionable recommendations for coaches, sports scientists, and sports medicine practitioners:

The multi-year national sports science program described in this review demonstrated that integrating genetic profiling, pharmacogenomics, immune monitoring, growth factor biology, biosensor assessment, and anti-doping methodology within a single applied framework is both feasible and scientifically productive. The program's findings regarding genotype-performance associations, pharmacogenomic-guided supplementation, and training-load-dependent immune dynamics have been broadly validated by subsequent research.

However, the field has also advanced beyond the methodological boundaries of the original program. The transition from candidate-gene studies to GWAS and whole-genome sequencing, the emergence of epigenomics and multi-omics integration, and the development of next-generation wearable biosensors have expanded the toolkit available for precision sport science. The next frontier lies in the development of integrative bioinformatics platforms capable of synthesizing genomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and phenomic data into actionable, individualized athlete profiles--a vision that the national program, in its integrative design, anticipated.

Future research should prioritize large-scale, longitudinal, multi-omics studies that integrate genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolomic, and epigenomic data within diverse athlete populations. Such studies will require international collaboration, standardized phenotyping protocols, and robust bioinformatics infrastructure, but hold the promise of transforming sport science from a population-based to a truly individualized discipline.

| Component | Methods | Key Findings | Current Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Polymorphism Analysis | qPCR genotyping for 8 loci (ACE, AGT, ACTN3, AMPD1, MYH7, VDR, COL1A1, CALCR) | AGT, AGT2R1, ACTN3, AMPD1 significantly associated with performance phenotypes | Validated by multiple meta-analyses (Ahmetov et al., 2022; Semenova et al., 2024) |

| Pharmacogenetic Profiling | DNA microchip for CYP450 and GST genotyping | Significant inter-individual variation in colostrum/BCAA response by CYP/GST genotype | Ahead of its time; pharmacogenomics now standard in clinical medicine but still emerging in sport |

| Immune Monitoring | Flow cytometry; qPCR for cytokines; viral load quantification | Training load correlated with immune suppression; NK cell decline and CD4/CD8 ratio inversion documented | Validated by subsequent studies (He et al., 2021; Soares et al., 2021) |

| Growth Factor Biology | Affinity isolation of GH isoforms; IGF-1 correlation studies; MGF detection in muscle biopsies | MGF detected exclusively in working/damaged muscle; selective myoblast proliferation confirmed | MGF remains on WADA prohibited list; IGF-1 pathway research continues to expand |

| Biosensor Assessment | Stabilometric platforms; isokinetic dynamometers; universal assessment scales | Sport-specific normative ranges established; cross-sport comparison enabled | Force-plate and isokinetic technology continue to advance; wearable sensors now complement |

| Non-Invasive Biomarkers | Spectrophotometric analysis of exhaled air, saliva, and skin emissions | Method validated against laboratory biomarkers; aerobic/anaerobic threshold assessment enabled | Exhaled breath analysis validated; wearable sweat sensors approaching clinical grade |

| Anti-Doping Methods | Express steroid screening; HBOC detection; gene doping PCR assay | Three novel detection methodologies developed for national anti-doping use | Gene doping test approved by WADA (2021); CRISPR-Cas12a platform achieves 4x greater sensitivity |

Table 4. Summary of Program Components, Methods, Key Findings, and Current Status

The author declares no conflicts of interest. No external funding was received for this work.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). Readers may share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, provided appropriate credit is given.

Citation: Andreev, R. (2026). Genetic markers for talent identification and training individualization in elite combat sport and endurance athletes: Insights from a national sports science program. American Impact Review, e2026005.

Roman Andreev, Sergey Razinkin (2026). Genetic Markers for Talent Identification and Training Individualization in Elite Combat Sport and Endurance Athletes. American Impact Review. Retrieved from https://americanimpactreview.com/article/e2026005