1. Introduction

High-load systems (HLS) form the backbone of modern digital infrastructure, processing millions of concurrent requests across financial platforms, social networks, e-commerce marketplaces, and cloud computing environments. The global cloud infrastructure market exceeded $270 billion in 2024 (Gartner, 2024), with availability expectations approaching "five nines" (99.999%) for mission-critical services. At this level, the permissible annual downtime is approximately 5.26 minutes -- a constraint that transforms monitoring from a passive observational activity into an active, mission-critical engineering discipline.

The fundamental challenge confronting HLS operators is the tension between two competing imperatives: resource efficiency (minimizing computational cost) and service quality (maximizing user satisfaction as codified in SLA agreements). Monitoring bridges these imperatives by providing the informational substrate upon which scaling decisions are made. However, monitoring alone is insufficient; without mathematical models to interpret monitoring data and evidence-based frameworks to guide action, operators are reduced to reactive firefighting rather than proactive capacity management.

Several research gaps motivate this work. First, while individual monitoring metrics (latency, throughput, error rate) are well understood in isolation, their interdependencies under load are poorly formalized. Second, anomaly detection in HLS monitoring streams remains largely ad hoc, relying on static thresholds rather than statistically principled methods. Third, the evidence-based approach -- well established in medicine (Sackett et al., 1996) and increasingly advocated in software engineering (Kitchenham et al., 2004) -- has not been systematically applied to HLS scaling decisions. Fourth, while queueing theory provides a mature mathematical apparatus for modeling system throughput and latency (Kleinrock, 1975), its application to modern microservice architectures with auto-scaling capabilities requires adaptation.

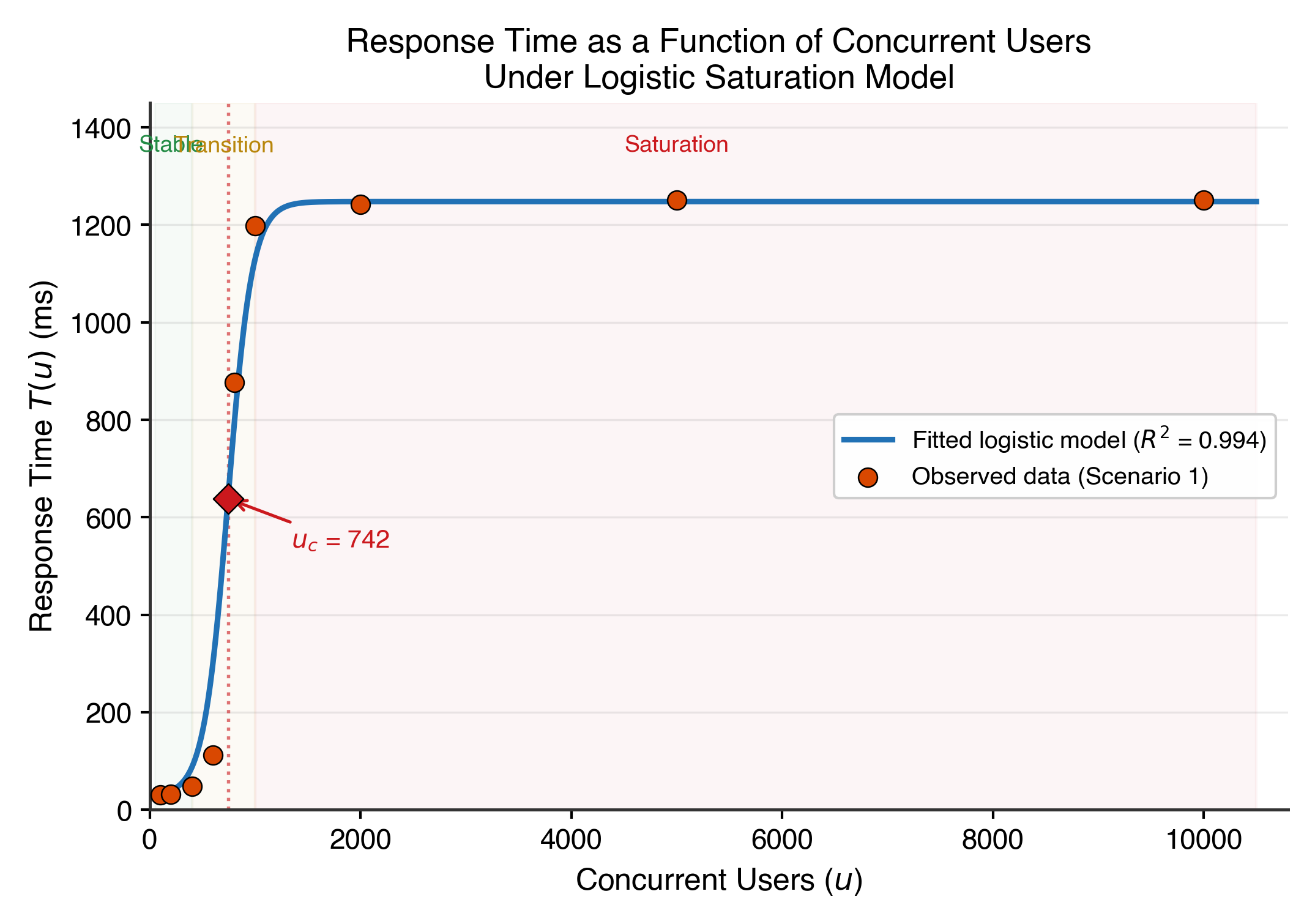

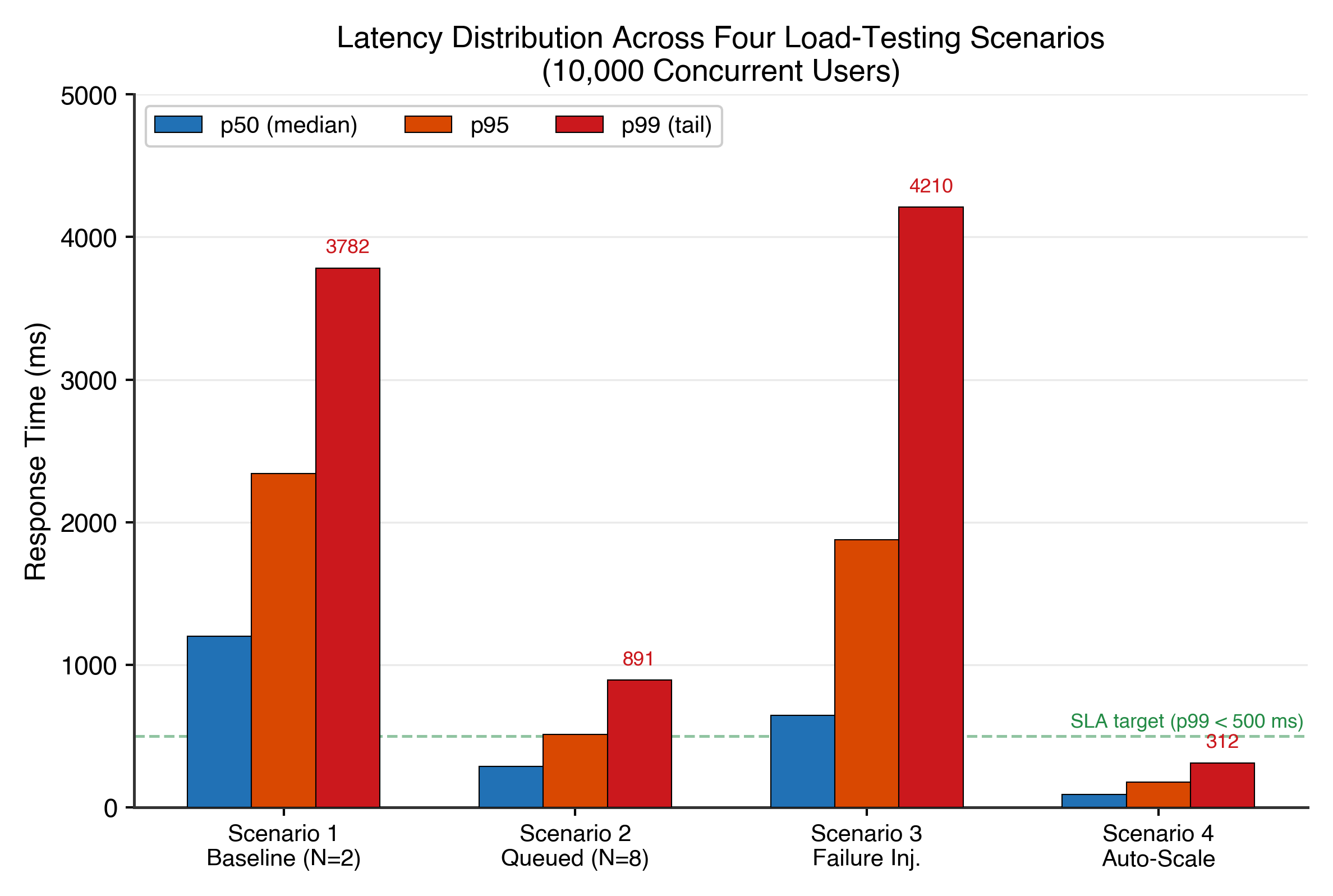

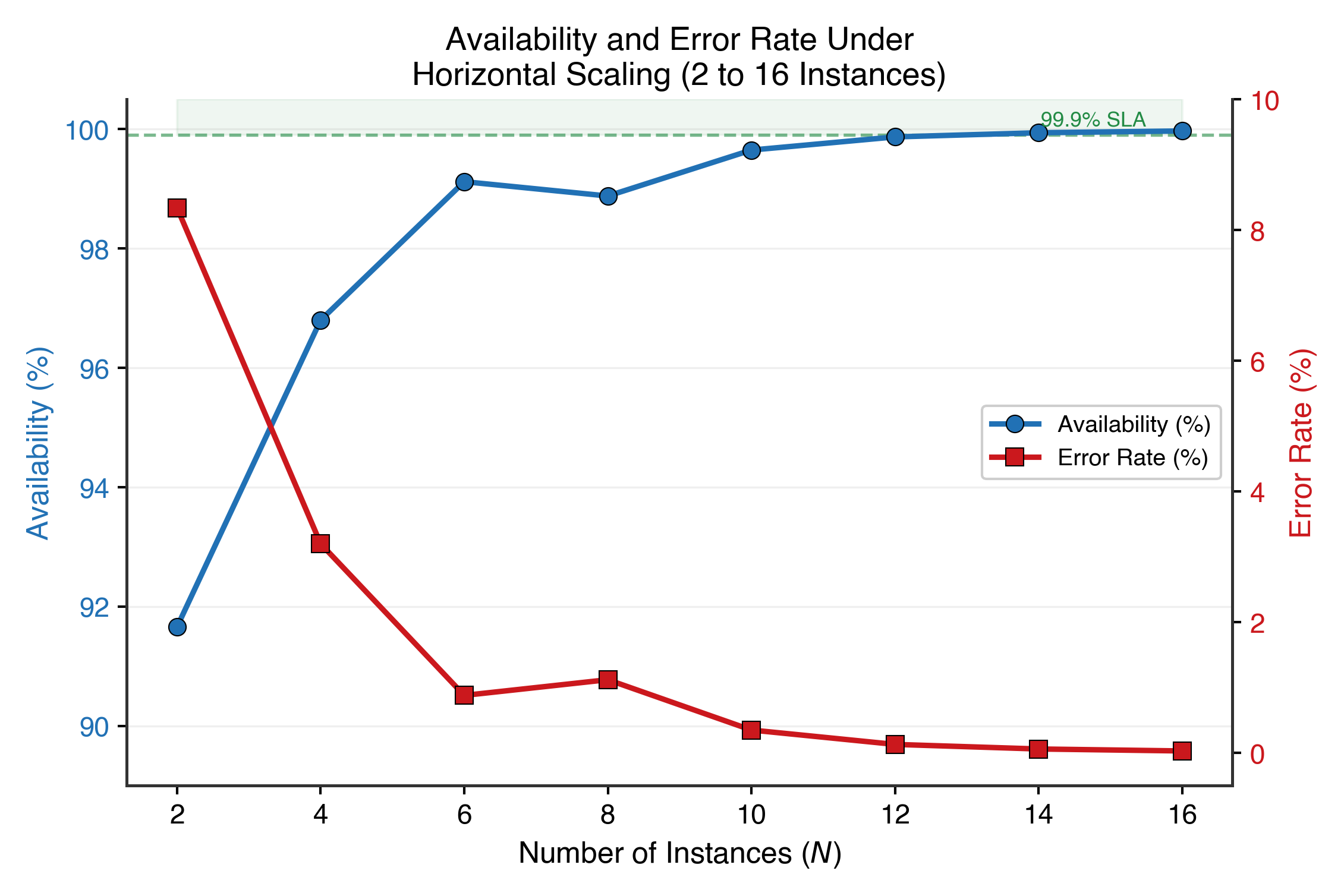

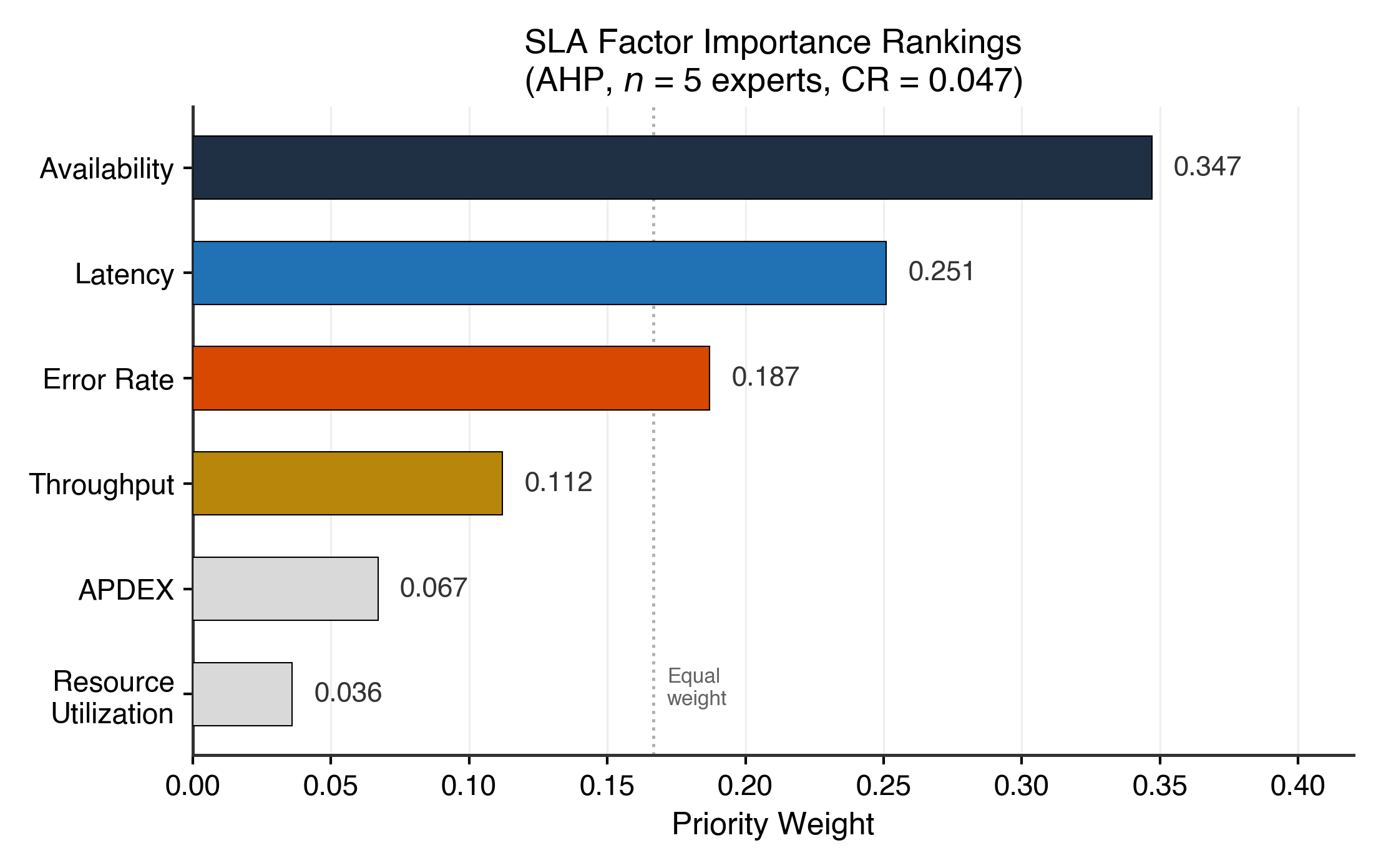

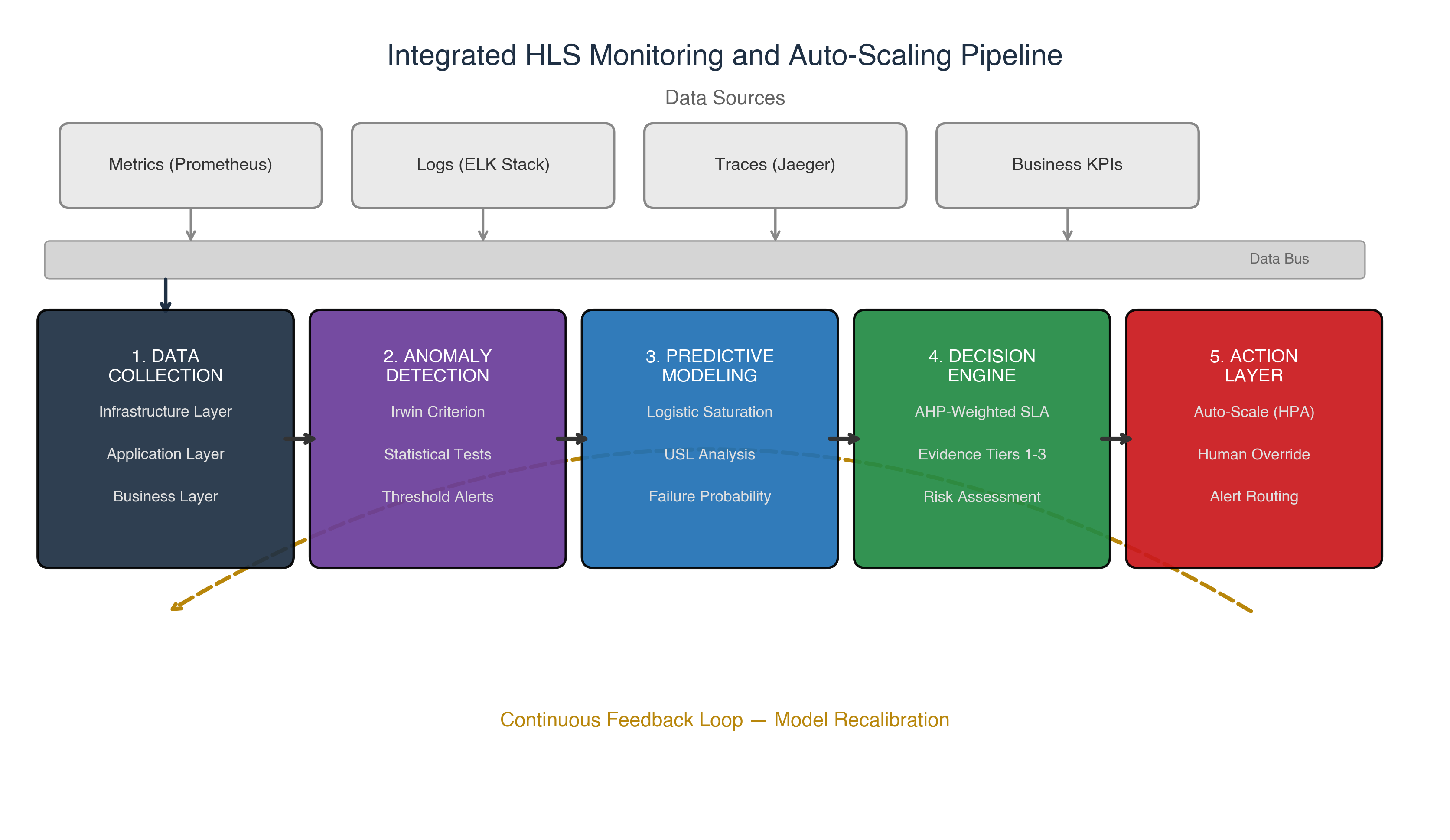

This article addresses these gaps by proposing an integrated framework combining: (a) queueing-theoretic formalization of HLS performance metrics; (b) a statistical anomaly detection procedure validated against empirical data; (c) a logistic saturation model of system throughput; (d) an Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) methodology for SLA factor prioritization; and (e) an evidence-based decision framework for scaling. The framework is validated through load testing of a production-grade microservice platform.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on HLS monitoring, scalability, and evidence-based approaches. Section 3 describes the methods, including mathematical models, experimental setup, and analytical procedures. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 provides a discussion encompassing theoretical implications, practical recommendations, and philosophical considerations regarding the limits of automation. Section 6 concludes with a summary and directions for future research.